For the past six years, Michael Schnur and his family have been drinking bottled water.

Regulators are studying whether to set limits for strontium, which is suspected of having negative health effects, especially for babies and children.

Already concerned that pollutants from the coal ash landfill near his home in Sheboygan County might be leaching into his private well, Schnur became even more fearful last year when he received a letter from the state Department of Health Services. It warned that elevated levels of a little-known, unregulated element — strontium — were found in his drinking water.

In follow-up email correspondence, the DHS said the landfill was not impacting Schnur’s water and that strontium occurs naturally in the groundwater. Schnur was advised to install a water softener, which works by replacing minerals like calcium, magnesium and strontium with sodium.

“I have a new baby (coming) in a couple months, which is why it’s really nerve-wracking,” Schnur said last spring. A healthy baby girl, Sophia, was born in August.

Schnur, who acknowledges he is no expert on water issues, remains on alert. His family continues to drink bottled water.

The federal Environmental Protection Agency has made a preliminary decision to begin regulating strontium.

However, in January, the agency delayed a final decision in order to collect additional information. The EPA wants to determine, among other things, whether treatment systems that remove strontium also would remove beneficial calcium, potentially making the effects of strontium on bones and teeth even worse.

EPA datafrom 2013 to 2015 suggest that some public water systems in eastern Wisconsin contain among the highest levels of strontium found anywhere in the country. Nationwide testing showed 73 of the 100 highest readings came from Wisconsin in communities including Waukesha, Brookfield, Germantown, Kaukauna, Wrightstown and Fond du Lac.

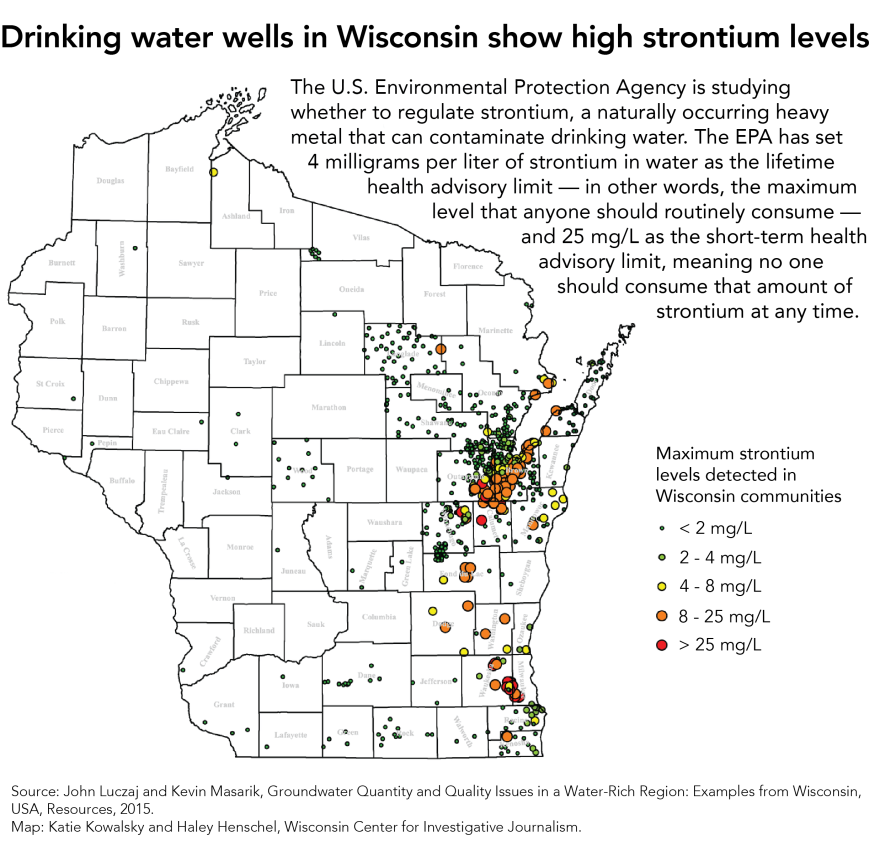

The EPA has set 4 milligrams of strontium per liter of water as the lifetime health advisory limit — in other words, the maximum level that anyone should routinely consume — and 25 mg/L as the short-term health advisory limit, meaning no one should consume that amount of strontium at any time.

Twenty-nine of the results found in the EPA testing in Wisconsin exceeded the EPA’s 25 mg/L short-term health advisory limit. The highest level from that round of testing was 53 mg/L in Germantown in 2013.

The level of strontium detected in Schnur’s well, 7.2 mg/L, is what DHS toxicologist Roy Irving described as “middle of the pack.”

University of Wisconsin-Green Bay geoscience professor John Luczaj said if the EPA confirms 4 mg/L as an enforceable maximum contaminant level, that would be a “big deal.” According to a study released in June by Luczaj and Kevin Masarik, a groundwater education specialist at the Center for Watershed Science and Education at UW-Stevens Point, strontium is present in the deep aquifer “throughout much of eastern Wisconsin.”

Hundreds of wells throughout the region are affected, including many municipal wells from the suburban Milwaukee metropolitan area north to Green Bay, they found. Particularly high levels were found in parts of Brown, Outagamie and Calumet counties, Luczaj and Masarik wrote.

Luczaj said that while water softeners and reverse osmosis systems can remove strontium, he does not believe that municipal water system customers can be forced to buy expensive treatment systems in order to safely drink their water.

Health effects unclear

As a currently unregulated contaminant, strontium is still a public health mystery. Limited studies suggest, however, that exposure to strontium at elevated levels could affect infants, children and young adults, as it mimics calcium and is absorbed by their developing bones.

Possible health effects from exposure to high levels of strontium range from “strontium rickets” — in which bones are shorter and more dense than normal — to other tooth and bone deformities, according to a Wisconsin DHS fact sheet.

The EPAsaid certain populations are more sensitive to strontium’s harmful effects, including people with calcium deficiencies, kidney conditions and Paget’s disease.

Bud and Vicky Harris have taken precautions against contaminants in their well water in the home where they have lived for nearly 20 years in the town of Lawrence near De Pere. He is a retired UW-Green Bay professor of natural and applied sciences and she retired from her job as a water quality specialist based in Green Bay for UW-Madison’s Sea Grant Institute.

It is good they took action. A test in 2012 showed 28 mg/L of strontium in the water coming into their home — above the maximum short-term exposure limit recommended by the EPA. A 2013 test showed 22 mg/L, slightly below that limit.

Soon after moving into their home, the Harrises installed a water softener, iron removal system and reverse osmosis system because they were aware of local drinking water problems, especially arsenic. Vicky Harris said the couple has spent thousands of dollars on water treatment systems to remove contaminants.

“For us, it’s worthwhile. Water is health. Water is everything,” she said.

Vicky Harris wonders about the untreated water their son drank from a private well in Allouez near Green Bay before they moved to their current home when he was 8 years old. Their son has mottled enamel on his teeth, which she said could be related to the fluoride also present in the Green Bay area.

Strontium levels high

Some samples collected from public water systems in Washington and Waukesha counties turned up strontium concentrations as high as 53 and 37 mg/L, respectively, well above both the short- and long-term advisory levels set by the EPA.

Still, exactly what this means for people living in affected areas is not yet clear.

In calculating safe concentrations, the EPA considers body weight, drinking water intake and the level of exposure to a contaminant believed to be from drinking water and other sources. Irving explained that it is important to note that these factors differ among people, as does their nutritional status.

“There are a lot of things that promote healthy bones, things like calcium, vitamin D,” Irving said. “Those all counter-balance risks from strontium.”

Said Luczaj: “Unless the strontium is very high, I wouldn’t worry about it.”

Where high concentrations were found in places including Cedarburg, Germantown and Kiel, water utility managers there said more than 90 percent of homes already have water softeners. It is unclear, however, how many people are drinking the softened water, which some people avoid because it has added sodium. While drinking softened water is not considered harmful for most healthy adults, people on sodium-restricted diets are advised to consider other options.

Strontium problem centered on eastern Wisconsin

The samples from public water systems in Wisconsin and around the country were collected as part of the EPA’s Unregulated Contaminant Monitoring Rule program.

Under the Safe Drinking Water Act, the agency is required to decide whether to regulate at least five unregulated contaminants every five years. The act sets mandatory standards for public water systems.

Previous studies have estimated that strontium occurs at levels of concern in 7 percent of public water systems in the country. That information, coupled with the knowledge of its potential health effects, led the EPA to make a preliminary decision in 2014 to begin developing strontium regulation.

Before the EPA began collecting data in 2013, however, Luczaj, the UW-Green Bay professor, conducted a regional study of wells, focused on Brown and Outagamie counties, to map the distribution of strontium in the eastern part of the state and determine its source.

In his paper published in 2015, Luczaj found high levels of strontium in “an arc-shaped band through eastern Wisconsin from suburban Milwaukee up through Brown, Outagamie, Calumet, Door, Oconto and Marinette counties.”

Although Luczaj does not consider strontium to be among the most significant groundwater contaminants, he said it is something people should know about. Whatever the danger might be, aside from a select few residents, there does not seem to be much concern about strontium from members of the public.

Since Luczaj’s study was published and covered by local media, Brown County Public Health Sanitarian Marty Adams said he has only received a call or two.

“I think a lot of people just don’t understand what it is and therefore not a lot of questions have developed about it,” Adams said.

Tests of Adams’ own well water have uncovered levels of strontium between 16 and 17 mg/L, far above the EPA’s long-term health advisory level of 4 mg/L. Due to the high levels of fluoride present when Adams’ well was drilled 20 years ago, he already had a reverse osmosis system and water softener installed.

Adams emphasized that for private wells, it is up to individual homeowners to have their water tested. One resource is the State Laboratory of Hygiene. A test for heavy metals, including strontium, lead, arsenic, manganese and other elements, costs $60.

People drinking municipal water may also want to do testing, as the EPA is not likely to begin regulating strontium anytime soon.

While Schnur has tried to get his neighbors to test their water, he said the interest just has not been there.

“I just wanted people to be notified of it — that there were high levels of strontium — and it doesn’t seem like anyone really cares,” Schnur said. “Each to their own. I’m just going to make sure my family’s safe.”

Reporters Silke Schmidt and Dee J. Hall contributed to this report. This story was produced as part of The Confluence, a collaborative project involving the Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism and University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication reporting classes. The nonprofit Center (www.WisconsinWatch.org) collaborates with Wisconsin Public Radio, Wisconsin Public Television, other news media and the UW-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. All works created, published, posted or disseminated by the Center do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates.