When Shiredon Roper and her children fled their home two months ago to escape a violent situation, they took shelter in abandoned buildings. Roper dared not sleep as she watched over her son, 15, and daughter, 10, she said.

Roper, a diabetic in stage-five renal failure with no local family, called 211, Milwaukee’s coordinated shelter entry system that prioritizes callers based on their level of vulnerability. After three days, she was offered and accepted a room at the Salvation Army Emergency Lodge.

IMPACT 2-1-1 Coordinated Entry for Homeless Services, implemented here in 2013, has improved the process for matching Milwaukee’s most vulnerable homeless people with shelter space, according to experts. But stories like Roper’s indicate that emergency shelter space is inadequate, especially for families with children.

Family shelter space is very limited, agreed Audra O’Connell, Impact’s Coordinated Entry program director. It is especially tight for larger families and families with challenging circumstances such as medical problems or disabled adult children who need parental supervision, she said.

Directors of nine local homeless shelters report that their facilities are currently full or near full. Eight of those are open around the clock and don’t require guests to leave during the day. The Cathedral Center is not usually open 24 hours, but in extreme weather, the staff works overtime to allow guests to stay all day, according to Donna Rongholt-Migan, executive director.

Eighty to 90 percent of people calling 211 seeking shelter do not fit the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s (HUD) definition of who is in need of immediate shelter, O’Connell said. Her staff strives to come up with alternative solutions to the problems that cause people to feel vulnerable, she added. Such things as utility assistance, landlord-tenant mediation and referrals to Wisconsin Works (W2), a program that provides job services, case management and cash assistance to eligible families, often allow people to stay in their homes.

O’Connell noted, for example, that many people don’t understand that the first eviction notice they receive is an order to come up with a “cure” (a payment plan, a plan to move elsewhere, etc.) in five days, not an order to vacate.

Impact assesses the situation of each caller seeking shelter. Then O’Connell’s staff matches “those most likely to die in their current situation” (category 1) with available shelter beds or warming centers, she said.

On a recent day when the high temperature hovered near zero, Impact received shelter requests from 12 families it classified as category 1 homeless, said O’Connell. All who could be reached by phone or text were offered shelter or warming rooms that day, O’Connell said. For those put in warming rooms, Impact continued to search for shelter space. Shelters are preferable because, in addition to offering social service programs, families can sometimes stay for up to 90 days, she added.

In 2014, the last year for which complete figures are available, Impact received calls from 3,409 families seeking shelter. According to Impact’s assessment guidelines, 340 to 680 families needed immediate shelter, an average of 6.5 to 13 families per week. On average, Impact cannot find shelter for about half the families on the day they call, O’Connell said.

With a number of warming centers open during the recent cold snap there is currently some kind of shelter available for most of the homeless people in the city, she said. But for families with children at school and in daycare centers, gathering up the family and finding transportation to a shelter is difficult and sometimes impossible. O’Connell said she has brought this to the attention of government officials and funders and hopes this gap will be filled.

The coordinated entry approach initiated by HUD and required for shelters receiving federal funds, has improved the process of getting the city’s most vulnerable homeless people into shelter, said Faith Kohler, a homeless advocate, volunteer and director of the film “30 Seconds Away: Breaking the Cycle,” about homelessness in Milwaukee. The system “does a better job of filtering who is in emergency and who really is on the street, homeless, versus who may be able to wait for a better option that will be available shortly,” Kohler said.

Since calling 211 does not work with some flip-style cell phones, Impact is also publicizing a local phone number: 414-773-0211; and a toll-free number 1-866-211-3380. Calls are taken 24-hours a day, seven days a week.

Adelson Thompson and his wife and sons, ages 9 and 13, needed shelter last summer. Thompson, 45, lost his job as a certified nursing assistant in February and started to fall behind on his rent. He went to court to try to work out a payment arrangement.

“I was trying to get my unemployment going, W2, somebody to help me. It took a while and by that time, we were (further) behind in rent,” he explained. By June, unable to catch up with their bills, the Thompsons got an eviction notice. Thompson understood it to be an order to vacate in five to seven days, he said. He called 211 every morning for five days until his family was offered shelter at Hope House of Milwaukee, 209 W. Orchard St.

“I almost broke down and cried (when I got the call). I didn’t know where we was going to go with our kids … My sons go to Longfellow School and they’re straight A students. I didn’t want anything to interfere with their education,” Thompson said.

Several shelter directors noted that there are fewer people seeking shelter early in the year. Many low-income families and individuals are eligible for earned-income tax credits and get tax refunds at the beginning of the year, explained Patrick Vanderburgh, Milwaukee Rescue Mission president. In addition, laws prohibit energy companies from shutting off power from November through April and it’s harder to evict tenants in winter, he added.

Also, people are more receptive to sheltering others in cold weather, said Nancy Szudzik, director of homeless services at Salvation Army Emergency Lodge. But in summer when children are not in school, their constant presence can cause friction with hosts sheltering homeless family and friends.

O’Connell noted that when people who consider themselves in crisis call Impact, their circumstances may be fluid. They will often refuse shelter placement, instead making their own arrangements for a temporary place to stay that eventually falls through. “This is very difficult to navigate as we try to place people and they refuse space for something less stable,” O’Connell said.

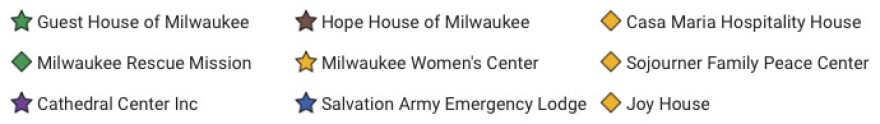

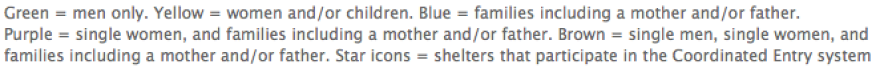

The shelters participating in the Coordinated Entry system are: The Cathedral Center, Guest House of Milwaukee, Hope House of Milwaukee, Salvation Army Emergency Lodge and Milwaukee Women’s Center.

Faith-based shelters do not receive federal funds and are not part of Impact’s Coordinated Entry system though anyone seeking shelter is invited to call 211 and Impact’s staff will notify them if space is available in independent shelters.

You can find other stories about Milwaukee's central city at Milwaukee Neighborhood News Service.