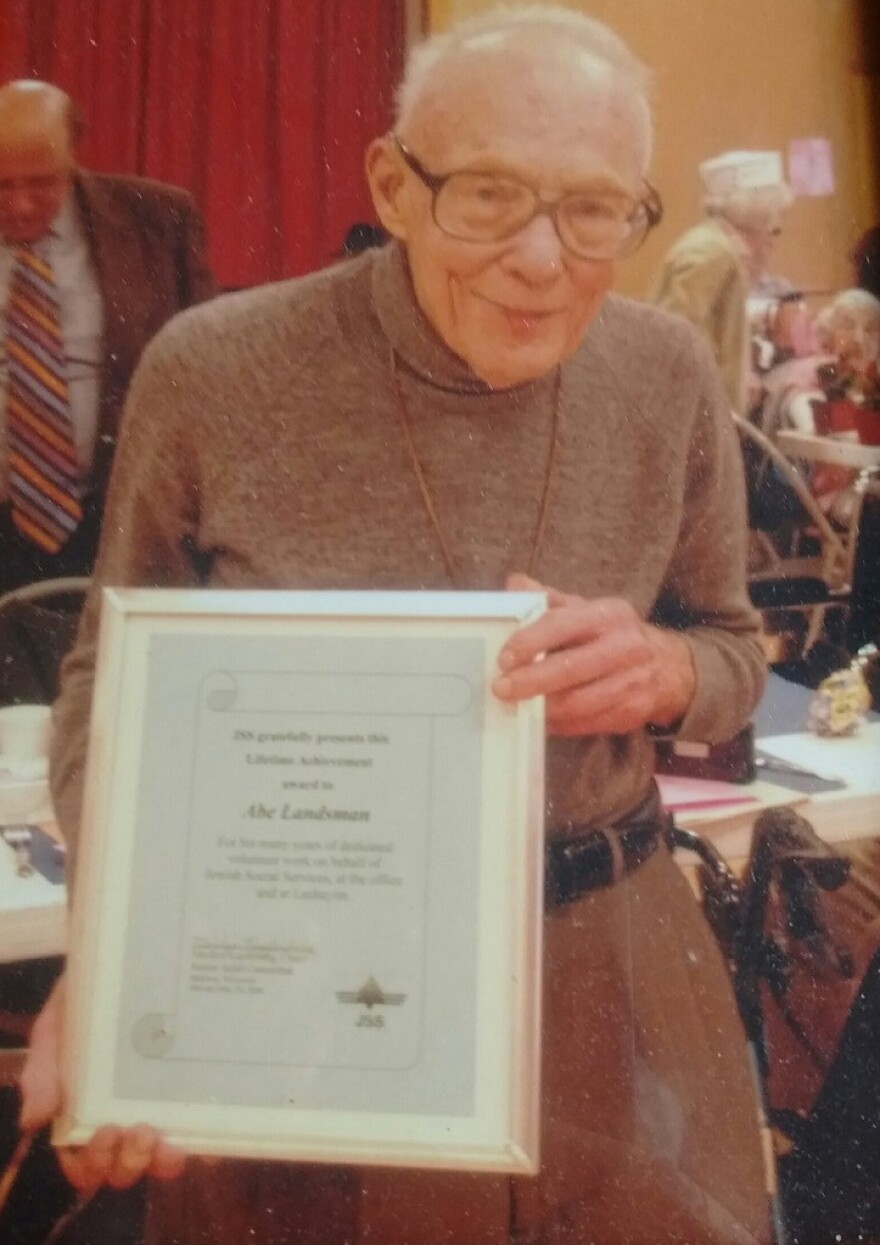

This piece originally aired June 2, 2016. Abe Landsman, age 102, passed away September 2, 2016, peacefully at his home in Madison.

A couple of videos went viral in the last few weeks featuring some of America’s oldest citizens. One was of a 92-year old World War II veteran who threw out the first pitch at a Major League Baseball game on Memorial Day.

The other was a 106-year woman who got to visit with the President and First Lady, and used the occasion to dance in the White House.

The grandfather of Lake Effect contributor Jessie Garcia isn’t quite that old, but at 102, can certainly claim the title of “one of Wisconsin’s oldest residents.” Jessie recently stopped in to see him, and gain some insights into life, death, and our overall well-being:

I'm in the parking lot of a retirement home, on my way to visit my 102-year-old grandfather.

He's not my real grandfather - as in, a blood relative. He's the father of my step-father, a man I met when I was 10 years old. But he has been a grandfather to me ever since - sending my elementary school self clippings about the movie E.T., saving things out of his treasured reader's digests he thought I might find interesting and always, always telling me he loved me. I refer to him, and always have, as "Abe."

His full name is Abraham Landsman. Born in 1914. He was my age two years before John F. Kennedy was elected. What mind-boggling changes he has witnessed from pre-World War I to now.

It's been a few months since I've seen Abe and I'm anxious to give his bony frame a big hug.

Abe moved from Florida to Wisconsin to be near all of us shortly after his wife passed away in 1990. Immediately he took to Madison, learning the bus routes, gaining a girlfriend...and then another when the first passed away - and always dancing, lifting weights, reading and being a full participant in life. He became a front desk attendant at the Madison Senior Center and earned an award as the oldest worker on the city's payroll at the age of 88. But he wasn't ready to stop. Not even close. Abe worked seven more years until finally retiring at the age of 95.

Now at 102, we all know he's over the usual expiration mark. I'm blessed to have had Abe for this long and he remains lucid in mind, even if his body hunches over a bit. Up the stairs I walk in my clunky clogs to his floor.

I have rarely seen Abe in anything but dress pants, solid leather loafers and a clean and pressed shirt. Today is no different. He is in the reception area in his wheelchair, pouring himself a cup of coffee in a plastic cup. The nurse tells me he's been watching the clock - and I'm five minutes late.

We hug and - using his feet for power instead of his hands - he rolls himself to his studio apartment down the hall. Settling in, he’s ready to chat, his hearing aids turned up, his glasses on and the plastic cup of coffee still in his hand.

I have so many things i want to ask him. Big picture stuff too. After all, most of us don’t live past the century mark.

"Do you have a sense how long you’ll live?"

"105. There’s no reason why I shouldn't go 3 more years, at least 3 more years."

"What’s the first memory you have of your life?"

"When I was about 3 years old a cousin who was probably ten years old used to come over in Bronx, New York City and he’d play with me. He always brought a long a handmade airplane."

"What do you think the biggest change has been in 102 years in terms of innovation for American lifestyle or global lifestyle?"

"Probably the computer, the computer changed everything."

Abe has a computer, gathering dust in the corner of his room. He claims something is always broken on it.

"I use it as a glorified word processor."

"What would you say has been the secret to a long life?"

"Maybe 30% natural and the rest is probably diet, our diet was mostly fruits and vegetables."

"Do you still lift weights and exercise?"

"I should, but I don't do it. The only thing I have a bicycle over there that I use for 40, 50, 60 revolutions every morning."

"Do you still eat oatmeal every day?"

"Every morning, I still eat oatmeal every morning."

"How many years now?"

"Probably 80 years at least."

"Maybe that’s the secret to longevity?"

"I think that is one secret. Diet, love, friendship."

"I wanted to ask you about some of the happiest days of your life—what would you say if I asked you that?"

"When I got married when the children were born."

In 1976, Abe’s daughter Marcia told her parents she was gay.

"You remember that clearly?"

"Very definitely. There’s a picture here I think leading a gay parade."

Abe and his wife marched in the front of a gay pride parade not long after.

"You just wanted to support Marcia?"

"Oh yeah."

One of the great tragedies of Abe's life is that the same daughter, Marcia, died of non-smoker's lung cancer at the age of 59.

"I think we are born with genes, from the day we’re born the genes are there and it just takes time to erupt. The good lord in his funny ways, or her funny ways, has planned this."

"Can I ask you your thoughts on death? I’m wondering what you think happens after we die?"

"(Laughs) I don’t think about that. It happens, it’s not within our power to do anything about it."

"You don’t worry about death? You don’t fret about it?"

"No, if it comes, it comes. I have a do not resuscitate. Why did you choose to have that? I said enough, 105 is enough."

Abe is one of the oldest men in the assisted living home where he lives. He sits at meals with three women, who sometimes drive him crazy with what he considers childish issues.

"You’re sitting in my seat, that’s my seat, get off!"

"They argue about seating arrangements?"

"Yeah."

Ever since Abe’s longtime girlfriend died, he has been looking for another romantic companion—without success.

"I went around asking—nobody’s interested. Just to get together and hug, kiss...most of the people living here are in their 90’s already - don’t they miss that closeness also?"

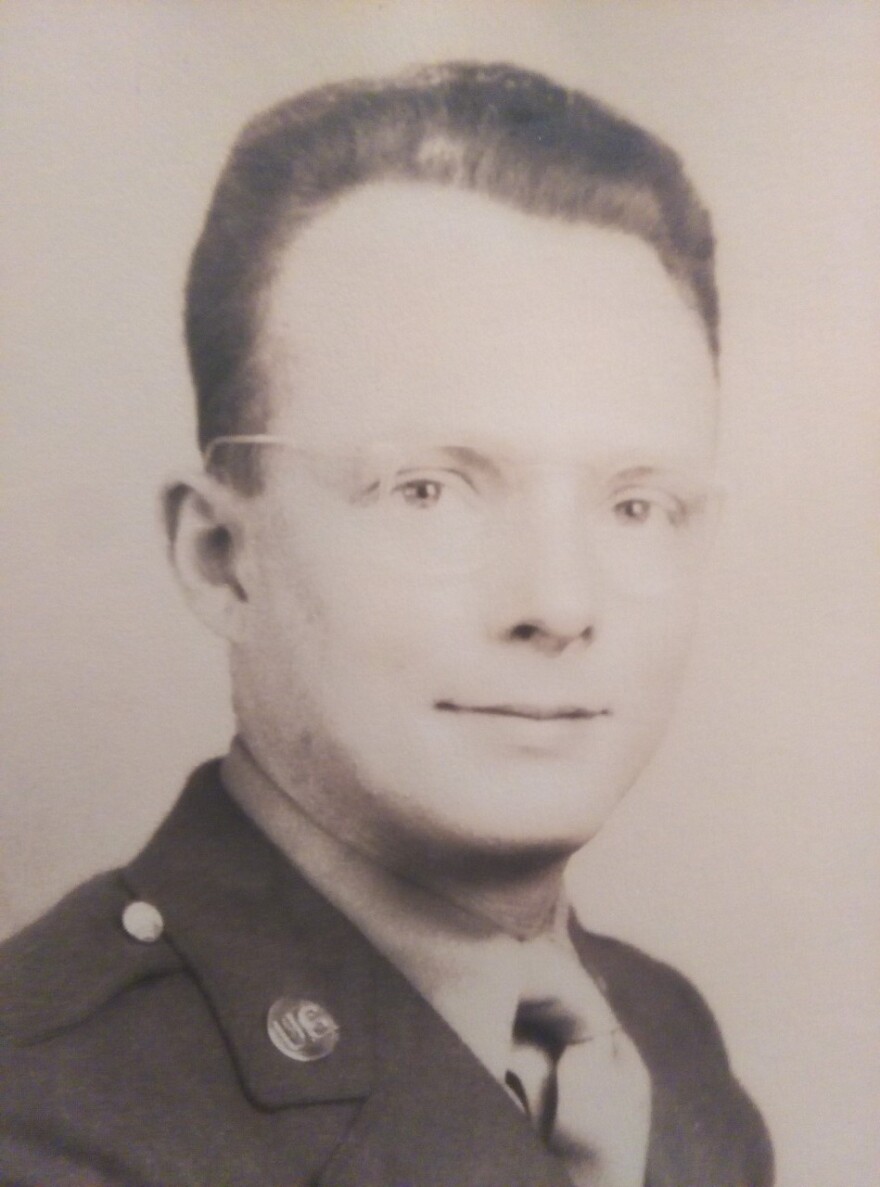

Abe served in World War II but avoided combat because he was able to type well.

"Six months later they made me company clerk and it saved my life."

"Would you say you’ve had a good life?"

"I think so, raised two wonderful children although Marcia unfortunately had cancer."

"When you look back at your life do you have any regrets or not?

"I don’t think I have any regrets—could I have done this? Could I have done that? Could I have done more or was I trying to do too much?"

"If you live to be 105, 3 years from now—is there anything you would want to say to your loved ones before you pass?"

"No, it seems to me you’re doing what you like to do, you’re not killing people, you’re leading a good life. It’s a good life out there if you make it good for yourself."

Abe has only two grandchildren—me and 18-year-old Emma, who was adopted by Marcia before she died. Abe’s bloodline will not continue but he has been a wonderful grandfather. As we wrap up our conversation, I lean closer to his wheelchair, the slight smell of coffee still on his breath as I kiss his cheek.

"I love you."

"I love you too, I'll see you soon."

We are leaving and he is getting ready for lunch with the ladies. He still can’t believe the amount of energy they put into who sits where and why.

"If you sat there all the time and somebody else sits there, so what? It’s only a chair."