Raise your hand if this is how your typical Friday night goes: If you aren’t ill or out of town, you are probably somewhere like the North Shore American Legion Post 331 in Shorewood. You might be meeting friends after a long week at work. You’re probably there for a beer or an old fashioned (make mine a brandy sour, please). And, you are definitely there enjoying a fish fry.

Our beloved fish fry is what makes Friday nights extra special in Milwaukee – and around the entire state of Wisconsin.

The meal most likely consists of cabbage, rye bread, potato, and fish.

But, why? Why those sides? And, why are fish frys so popular here?

Those are the questions a couple of listeners submitted to Bubbler Talk, asking about Wisconsin’s love affair with the fish fry.

WUWM turned to culinary historian and Wisconsin Foodie host Kyle Cherek to find out.

“The history of the Milwaukee and Wisconsin fish fry you could trace, easily, through food history all the way back to canon law and the Vatican in 1249,” Kyle explains.

Wait – the Vatican?

“This is a Middle Ages thing,” he continues, “…long before Wisconsin existed as it does now.”

Now, the peoples who lived here before the Europeans arrived were undoubtedly eating fish, but it was when the Europeans, and specifically Catholic Europeans, settled here that eating fish on Friday was codified (only a small pun intended). And that goes back to that canonical law from 1249 that forbade eating meat on Fridays.

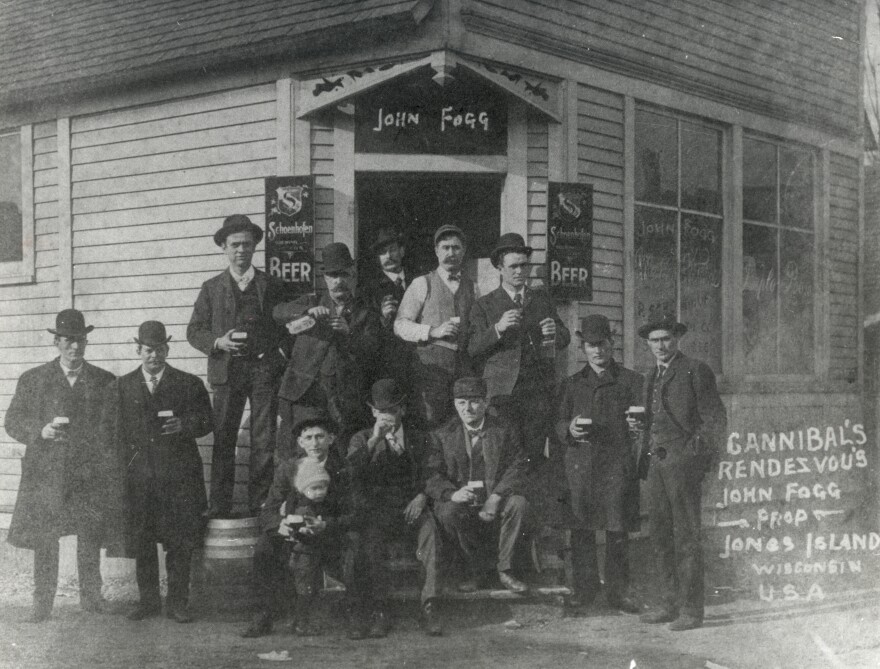

So did the fish fry start here? Kyle says, “Yes.” And most historians, including Milwaukee’s own John Gurda, point to Jones Island in the 1860s and ‘70s as ground zero.

“The Kashubes, who came from northwest Poland, Baltic Sea fisher people and settled on what is now Jones Island, were the first seminal fishers for Milwaukee. That’s what they knew to do and that’s what they came here and started doing. 1500 people with 11 taverns? Well, you know, they also served fish,” Kyle explains.

Events like the Civil War modernized boat technology and allowed the Kashubes and others on Lake Michigan to fish in deeper waters, increasing their catch.

And then there was Prohibition.

“If you’re a Miller or a Pabst or a Schlitz tied house, which is how taverns were, you sold that brewery’s beer to people who walked in. Well, how do you get them to come in if you can’t quote unquote sell beer?” Kyle asks.

“You sell a fish lunch, particularly on Friday,” he continues. “You get whole families to come in, you underprice it, you have it abundant, and if with your fish sandwich a modest beer is included because you’re thirsty and it’s a little salty? ‘Well, we’re just helping our customers out!’”

So we can thank teetotalers for the meal that made Milwaukee famous?

“We’re glossing over a lot of the aspects of prohibition, but that’s really what indemnified the Milwaukee fish fry and its success throughout the rest of the state. So between the canon law and no flesh meats in the Middle Ages through the Civil War through Prohibition, we end up with it being our statewide, and certainly our city, identity of a meal on a Friday night,” Kyle explains.

LISTEN: A Milwaukee Obsession: Sunday Hot Ham & Rolls

And, as for why our standard fish fry always includes the foods it does. The short answer: Fish, potatoes, cabbage (whether in coleslaw or cooked), and rye bread were cheap and plentiful. As we know, Milwaukeeans are nothing if not frugal, so eventually that combination of foods became the standard fish fry meal.

At the American Legion Post 331, we meet General Manager Diane Delland, who is herself a Kashube – her father was born on Jones Island.

“It was the poorest section of the city at that point, and my dad grew up there. We still have our family reunions on the little park there – yeah the fish market was right next to the park,” Diane remembers.

She says between sit down diners and takeout orders, Fridays are their busiest nights. The kitchen staff starts food prep at 8 am and isn’t done until after meal service ends at 10 pm.

“On a typical non-Lent Friday we do 200-250 fish frys. Like today we have a reservation for 24 that we’re prepping for and another reservation for 15 for 6 and 7 o’clock. We also can take large parties like that in the hall upstairs, but we have 12 tables in our dining area that are pretty much full the entire time,” Diane shares.

It’s a Friday scene that plays out in countless legion halls, restaurants, and supper clubs across the city and the state. The din of a fish fry in full swing is truly something special, Kyle adds.

“The conviviality of a the table that exists at a Milwaukee or Wisconsin fish fry is unlike any other meal that’s codified like that, that I’ve experienced anywhere. If you’re sitting at the end of one of the long tables and you don’t know the people across from you, you will within 7 or 8 minutes,” he says.

That, plus the fish, potatoes, cabbage, and rye bread, makes this a Milwaukee-born tradition worth celebrating.

Have a question you'd like WUWM to answer? Submit your query below.

_