One of America’s most famous lawyers of the 20th century was Ephraim Tutt. A public-service, justice-driven lawyer, he was known for his wild courtroom antics and brilliant legal maneuvers. Champion of the underdog, defender of justice and moral crusader, Tutt was the kind of compassionate and passionate lawyer everyone wanted on their side.

His cases were chronicled in books read by millions of readers, both lay and lawyer alike, and he even penned a best-selling autobiography. By the 1950s, this lawyer-with-a-heart-of-gold was nearly as well-known as Clarence Darrow, the defending lawyer at the Scopes Monkey Trial.

Tutt's only fault? He didn't exist.

Rather, he was the invention of Arthur Train, a Harvard-educated lawyer turned fiction writer who not only turned Tutt into a household name, but also pulled off one of the greatest literary hoaxes of all time.

The whole story is the subject of the new book The Myth of Ephraim Tutt: Arthur Train and His Great Literary Hoax, by author and lawyer Molly Guptill Manning.

Creating Tutt

Arthur Train (1875-1945) was a Harvard law graduate and assistant district attorney. While he was working on actual cases, Train saw people who were being sent to jail for doing things that were against the law, but would have helped out others.

Though he couldn't in real life, Train remedied these situations in his fictional stories through the character of Ephraim Tutt, a pro-bono lawyer who sought justice in every case using tricky trial tactics.

“Ephraim Tutt was just a really powerful symbol to a lot of people," Manning says. "And then when the country went into war during World War II in the 1940s, Ephraim Tutt had basically become a symbol of America."

The first Tutt stories appeared 1919 and were published through the Great Depression and into World War II. Manning says Tutt's courtroom victories made readers feel better, especially when the country was in upheaval. As the economy collapsed, the Dust Bowl ruined crops, and Pearl Harbor was attacked, American's illusion that the United States was untouchable was dashed.

“The idea that there’d be lawyers out there who would take their case for free and who would help them get back on their feet for free, and make sure that all the wrongs that happened to them would be righted," Manning says. "It really just made them feel hopeful for the future.”

Plus, the legal strategies Tutt used in the novels were based on real laws and cases, based on Train's experiences.

“As you read the story, it would almost seem that Tutt would have to lose the case. But then he would pull out some kind of legal argument that people never thought of and he would win," Manning says.

Many lawyers even kept Tutt's published "casebook" on hand, and Manning says some borrowed his strategies to use in real court cases.

The hoax

In the early 1940s, Train’s health started to decline and he realized that he would not able to continue writing Tutt novels. Manning says Train was so connected to Tutt that “he wanted to make sure that people had something to remember Tutt by…and that his legacy was Tutt’s legacy.”

So Train reasoned that if he couldn't keep writing Tutt's story, then Tutt would have to do it himself.

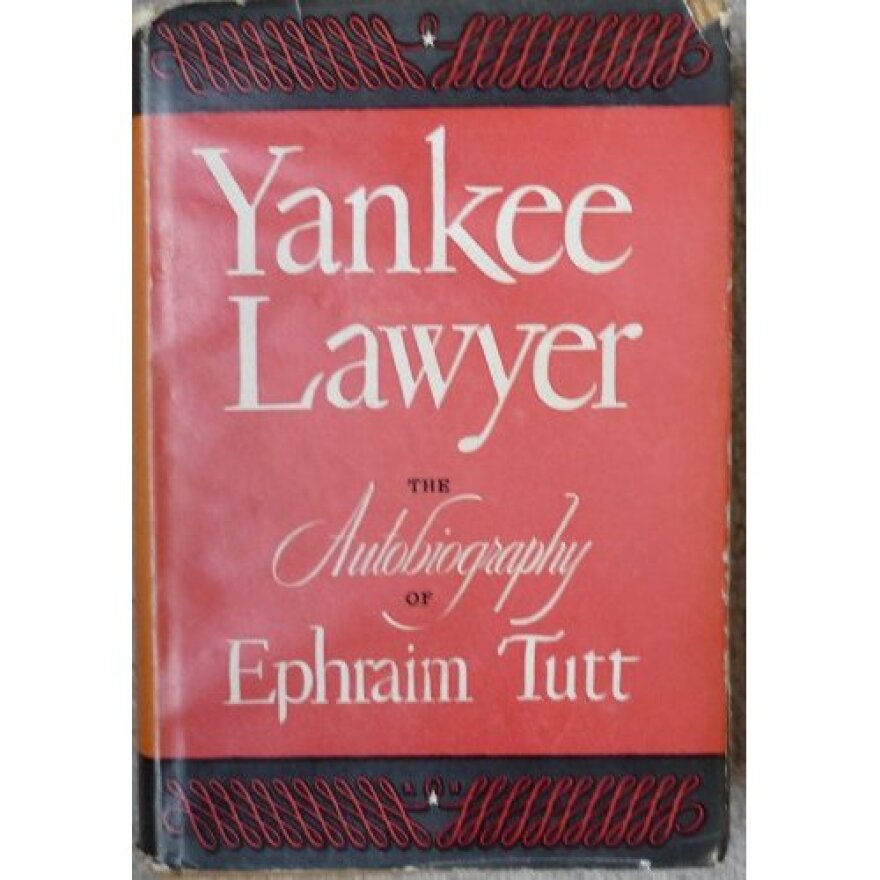

n 1943, Tutt’s “autobiography” Yankee Lawyer was published and marketed as nonfiction. In the introduction, written by Train, he said that Tutt had been his best friend for forty years and that he convinced Tutt that writing the autobiography was a good idea.

Train continued the subtle humor in the autobiography, having Tutt correct Train in his recounting of Tutt’s courtroom antics. Manning says even pictures from Train’s family’s photo collection were used in the book to create a visual representation of Tutt.

Copies sold quickly. Manning says the book reviewers, who understood that Train wanted to market this as an autobiography, played along in their reviews. Most of the readers grew up with the Ephraim Tutt series and appreciated the “autobiography” of their heroic, but ultimately fictional favorite lawyer.

But Manning says Train received quite a few letters from confused readers questioning whether or not Tutt was a real person. Whenever he received letters from readers, he would respond through a letter “written” by Tutt, keeping the illusion of Tutt’s true existence alive. As more letters came in, Train waited over six months after the book was published to restate that Tutt was a fictional character.

Manning says Train probably wasn't intentionally trying to pull the wool over his readers' eyes. She says one of his major reasons for writing Yankee Lawyer was to encourage lawyers to use their practices for good rather than focusing on making money.

But she says he may have kept the ruse going because he enjoyed the publicity he was getting. That said, Train did put that publicity to good use. In order to raise money for war bonds, Train suggested his publisher auction off a top hat and cane that had been used for a Tutt window display. Of course, in advertising the items as Tutt’s “actual” effects, Train helped perpetuate the idea that Tutt was a real man.

Court case

But Train soon found himself on the wrong end of a Tutt-related court case. An irate reader sued Train after he read the book and then the article Train wrote to clarify that the "autobiography" was actually written by him, not by the fictional Tutt.

The prosecutor’s complaint was that the book was promoted as nonfiction and therefore false advertisement. The media, which had in many instances played into the gag, was on Train’s side and mercilessly mocked the reader. Unfortunately, Train passed away before the case was fully resolved.

"In the end, he escaped liability," Manning says.

Despite the hoax, readers still loved Tutt - and Train, by extension - because he was somebody they could believe and trust, and rely on for advice and motivation when life dealt a bad card. The image of Tutt, like Perry Mason, carried on through to radio and a select number of television shows.

And so the Train/Tutt legacy remains untarnished to today.