As freeway routes were constructed in the 1960s, lots of Milwaukeeans were impacted — houses were demolished, businesses had to relocate. In part due to the upheaval, some communities still haven’t recovered decades later.

One of our community members heard stories about a freeway spur running through Milwaukee’s central city in the 1960s and wanted to know more. So, she submitted the question to Beats Me — our series that allows you to ask questions about race, education, innovation and the environment.

"Why was the freeway spur run right through the at-the-time vibrant central city neighborhood?"

Beats Me: What Questions Do You Have For WUWM's Beat Reporters?

Ben Barbera, curator and operations manager at the Milwaukee County Historical Society, says talks about a freeway system began as early as the 1920s.

"As automobiles were becoming more popular, they realized that the street system wasn’t designed for automobile traffic, and there was a lot of gridlock and other issues happening as more and more people were driving. But it wasn’t until the 1940s that the city really started to begin planning for an expressway system," he explains.

Barbera says additional factors contributed to the freeway plan, including the post-World War II economic boom as soldiers returned home. Some people moved to the suburbs but still needed to get downtown to their jobs.

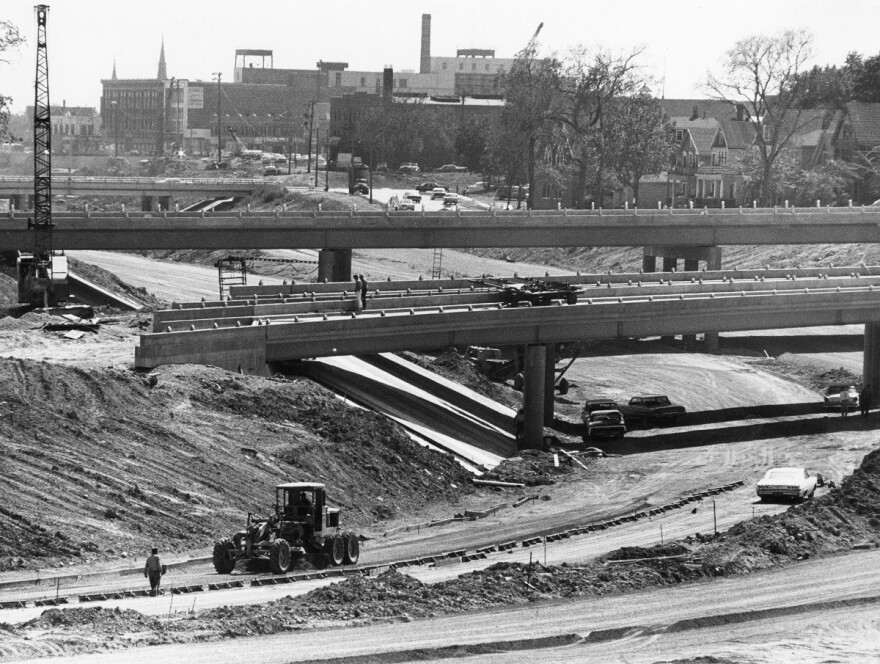

Planning and construction got underway and most of the major freeway construction was completed in the 1960s.

The freeway routes we drive today, Barbera says, reflect the vision that leaders had years ago.

"So, you’ve got the north-south and the east-west routes of 94 and 894 — those were the ones that they’ve identified primarily — and then a north-south route that is now 43, running up to the northern areas," he says.

It's the Interstate-43 route that runs through central city neighborhoods, which were at the time — and still are — predominantly African-American.

"Roughly between 1960 and 1969, roughly 17,000 homes were dislocated for lack of a better term, eradicated. And business numbers are a little bit harder to pin down, but there could be as many as 1,000 businesses were affected," Barbera says.

The freeway did not run through Bronzeville — then the city’s premiere African-American business and entertainment district. However, the nearby construction did impact the district.

It wasn’t just African-Americans who felt the effects of the I-43 project. But Barbera says they were disproportionately affected compared to the German, Jewish and white residents living in the area.

Andre Lee Ellis, a community organizer and founder of We Got This MKE, was a child at the time and remembers the neighborhoods changing.

"My parents ... would talk with us about what was going on in the world, in life. I could tell that there was something not good about it," he explains. Ellis’ family was living in the Lapham Projects on 6th and Brown Streets during that time.

At first people were excited by the thought of the new expressway, he says, and what it would do to ease congestion. But soon, they noticed the consequences of the road construction.

"It was really more where you could intentionally see that they were interrupting the progress of black people. Black people were making progress, businesses were there and all of that was interrupted when the expressways came," he says.

"Black people were making progress, businesses were there and all of that was interrupted when the expressways came," Andre Lee Ellis recalls.

Ellis says the expressway disconnected black people by running right through neighborhoods and slicing east-west streets in half. He says that harmed commercial business, sending consumers elsewhere.

And he remembers how that made him feel.

"I remember thinking this is the first time that I realized the word poor and how poor people were treated. 'We’re poor. This how they do poor people. This how they do us.' That’s all I kept hearing," Ellis says.

As more and more people saw the downside of the freeway construction, they pushed back at plans for additional stretches.

Clayborn Benson, executive director of the Wisconsin Black Historical Society, says black people began to picket. And other communities responded as well.

"The white citizens in the Wauwatosa area saw all of the demolition and the construction going on, said, 'Stop, no more,' and they put pressure on the system to say we will not be forwarding through with this project," Benson explains.

Construction on other freeway projects stopped completely in the early '70s.

Today, we still drive on roads that were meant to be connected to the freeway. And you can still find maps that show the much more extensive freeway system that planners originally had in mind.

Support for Race & Ethnicity reporting is provided by the Dohmen Company.

Do you have a question about race in Milwaukee that you'd like WUWM's Teran Powell to explore? Submit it below.

_