In Milwaukee Public Schools, about 7,000 students spend much of their time learning in a language besides English. The district has an array of bilingual, dual language and language immersion schools.

On a recent morning at H.W. Longfellow Elementary on the near south side, first grade teacher Evadelia Aldape helps students wrap up a phonics exercise on "a" and "o" sounds in Spanish.

"Árbol, a la, oficina," Aldape says.

A few minutes later, the class switches to English to sing a song.

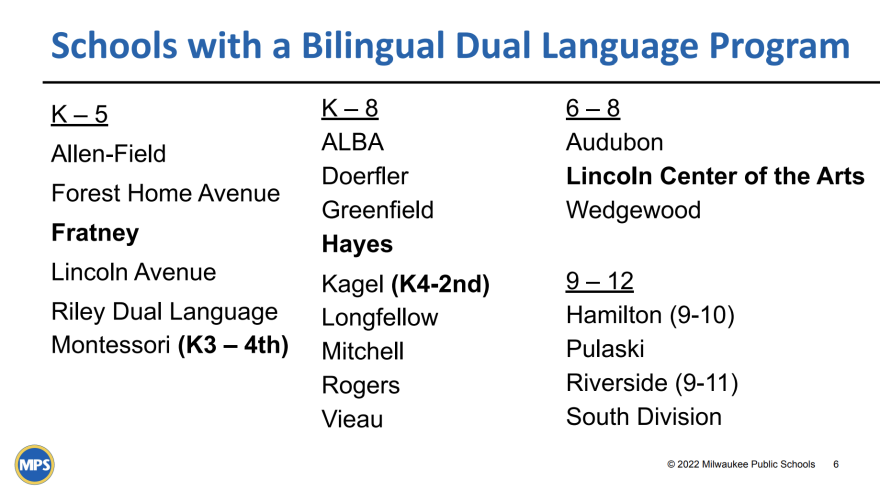

Longfellow is one of MPS’s 16 developmental bilingual schools, which are geared toward English learners whose first language is Spanish. MPS enrolls about 10,000 English learners throughout the district — more than half are Spanish speakers.

In the bilingual program at Longfellow, students start out with 90% of instruction in Spanish. When they get to Aldape's first grade classroom, 80% of instruction is in Spanish.

"We teach about an hour of English a day and then the rest is in Spanish," Aldape says. "The subjects that are in English are mostly health, science and social studies because it lends itself to it. But our main focus is to teach reading and writing and math in Spanish."

Aldape sometimes wears different color scarfs, as a visual cue for the language students should be speaking. Blue is for English, green is for Spanish.

English is phased in as students get older. Starting in fourth or fifth grade, instruction is half in Spanish and half in English. It’s known as a developmental, or maintenance bilingual model, where the goal is to maintain the student’s home language instead of phasing it out.

"The language is part of the culture of the child," says MPS Director of Bilingual Multicultural Education Lorena Gueny. "And we want to respect that culture by respecting the language."

MPS’ bilingual schools are the result of parent and community activism 50 years ago. Puerto Rico native Tony Baez was one of the Latino activists who pushed MPS to pay for bilingual education.

"The Latino community all over this country, not only in Milwaukee [was saying] immigration is increasing, and therefore, you should sustain language, and America should be bilingual like other countries," says Baez. "And you only do this, not by assimilating, but by growing their language, growing their culture, recognizing that this is OK, this is beautiful."

Using federal grant funding, MPS had piloted bilingual programs at a few schools starting in the late 1960s. They included Vieau, Lincoln and South Division. Baez says in 1974, at the urging of the community, the district committed to expanding bilingual bicultural programs to serve more English learners.

"And that became the envy of New York, California, Texas," said Baez. "I still remember people coming here and saying how did you guys do it?"

Baez says, in other states, school district leaders wanted to use transitional bilingual schools to assimilate Spanish speakers into all-English classes. In contrast, MPS embraced developmental bilingual education, which aims to teach students 50% in English and 50% in Spanish.

Now, the benefits of bilingualism are more widely recognized.

"When children are placed in bilingual settings, they outperform monolingual students academically, because they’re able to do academics in two languages," says UWM assistant professor and bilingual education expert Tatiana Joseph. "But they’re also able to think differently and process differently. And that affects the brain in a good way."

MPS later expanded its bilingual offerings to English speakers, with language immersion and dual language schools. The first was German Immersion School, in 1977. French, Spanish and Italian followed.

"All of the programs we offer are about language acquisition. But the language acquisition is instructed differently," says MPS's Lorena Gueny. "In the immersion, they start in the target language. If it is French, they start in French 100%."

Then there are the dual-language schools, also known as two-way bilingual. Those are for both Spanish- and English-speaking students.

In 1988, Fratney launched its dual-language program in the Riverwest neighborhood.

MPS Board President and former Fratney teacher Bob Peterson was involved in that effort.

"I strongly support bilingual schools, generally, but I also support integrated schools," Peterson says. "To accomplish that, one has a two-way bilingual program. The goal is to have 50% Spanish-speaking students and 50% English-speaking students, and they can learn from one another."

In 2020, MPS started offering high school students the opportunity to earn a Seal of Biliteracy by demonstrating proficiency in two languages. Milwaukee is one of just 14 Wisconsin districts to offer that certificate.

Tony Baez, who recently finished a stint on the MPS school board, has pushed for the district to expand bilingual programs in its predominately Black north side schools. Baez notes that bilingual schools are clustered on the south side, while most language immersion schools are on the western edge of Milwaukee, and serve a whiter student population.

"It's good for everybody, not just for Latino kids," Baez says. "If Milwaukee develops bilingual programs that reach everybody...the very act of learning a language gets kids to open up to learning."

Back at Longfellow school, eighth grader Estefany Rivera-Gomez says, as the daughter of Mexican immigrants, she didn’t learn to speak English until she was in kindergarten.

"I feel learning both English and Spanish makes me connect more to my culture," Rivera-Gomez says. "I feel like if I were to just be learning English, I would fall back in speaking Spanish, and I would lose my culture."

Estefany is glad she goes to a school where her first language of Spanish is seen as an asset, not a deficit.

Editor's note: MPS is a financial contributor to WUWM.

Have a question about education you'd like WUWM's Emily Files to dig into? Submit it below.

_