Religion offers people of faith many things including support and a sense of community. However, for LGBTQ+ people, their relationship with religion, specifically Christianity, can be difficult. Trying to live authentically within a system that may explicitly deny who they are can present challenges.

This piqued the interest of a couple Marquette University professors who researched what happens when two identities that seem in total opposition — conservative Protestantism and being LGBTQ+ — are joined together.

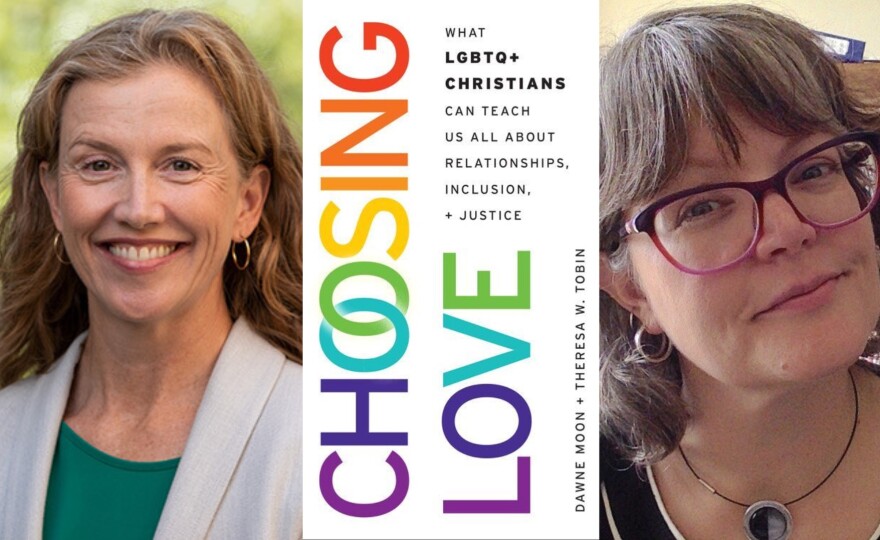

Dawne Moon is the director of Interdisciplinary Gender and Sexualities Studies at Marquette University & Theresa Tobin is an associate professor of philosophy at Marquette. Together they explored how LGBTQ+ Christians and their allies are working to make their families, churches and communities more inclusive in their book, Choosing Love.

Moon has been studying religion, gender and sexuality since the 1990s, but she started this project when she first heard about the movement among Evangelical LGBTQ+ people when an extended family member came out. "Other people in his immediate family were trying to figure out how they should respond and approached me and asked what I thought was the proper Christian response to homosexuality [even though I'm not religious,]" she explains. "But we started swapping articles and I learned that these organizations had started up and this movement was happening, and it just seemed like everything I had been studying in my life up to that point had come together."

This research lead to an opportunity to apply for a grant from the Templeton Religion Trust that required Moon work with someone in the humanities, which is where Tobin came into play.

Tobin describes herself as a moral philosopher working in contemporary ethics and social philosophy from a feminist perspective. "I've always been interested in ethical questions that arise at the intersection of people's faith experiences and spirituality and gender and sexuality," she notes.

As a practicing Catholic herself, Tobin says she grew up with a lot of questions around this intersection. In 2010, she was reading testimonies from survivors of the clergy sexual abuse crisis and many were naming spiritual violence as a type of harm from that abuse.

"The idea of spiritual violence [is] when your religion and your religious upbringing and authorities and rituals and practices are actually used to harm people spiritually and to erect barriers to their relationship with God. And I was so impacted by that term and I just thought, 'I want to study that more,'" explains Tobin. "So when Dawne approached me I saw these connections."

Choosing Love draws on participant observations and over 100 interviews conducted within organizations for LGBTQ+ Christians. This included LGBTQ+ Christians, former Christians, and allies -especially Black people, Indigenous people, and other people of color. These conversations led to the book focusing on four emotions in the lives of LGBTQ+ Christians: shame, humility, pride and love.

"One thing that started to become clear pretty early on was that an LGBTQ+ person had to constantly be displaying shame in order to be welcome in the group," notes Moon. "So we spent a lot of time looking at what is shame? ... And scholars across a whole lot of disciplines … they all come down to the idea of shame being a fear of being unworthy of relationships. So if you're having to constantly demonstrate [to] the people who matter most to you that you know you're unworthy of relationships in order for them to be willing to have a relationship with you and not just throw you out — then you're in this very difficult position."

Tobin says one thing that helped LGBTQ+ Christians come out the other side of the pain and difficulty of this imposed shame was pride, specifically relational pride.

"A lot of the folks we talked to were taught from very, very early on that pride is a sin and that it's one of the deadliest sins, maybe the root of all sin because they equate pride with arrogance, with sort of elevating yourself above God," she notes. "So what we learned from folks was the first step to healing seems to come through a kind of humility, which is an openness and prioritize what we can learn from our relationships to rethink ourselves and rethink what we know, or at least ask questions about it. That led many people to experience a kind of a sense of their own fundamental goodness and worthiness and that's the kind of pride we're talking about. “

Moon adds that this sense of humility also lent itself to better allyship for friends, family members of LGBTQ+ Christians and church leaders. "That allyship comes from both listening to the people that you want to be an ally to, loving them enough to actually learn from them and connect with them in a way that you can be transformed by your connection and not speaking for them," she explains. "You've got to listen to them and amplify their voices but also be open to learning new things.”

Diving into this research as a non-religious queer person, Moon hopes that people like her can learn from this book and this wider movement.

“I left the church as soon as I could basically and what I learned from this movement is not just about how to be a better Christian," she says. "It's about the things that are really easy for me as an outsider to see as toxic dynamics are also toxic dynamics that exist within the left, and I hope that more than just the people that the book is specifically about will want to read it ... You don't have to convert religions to learn from them."

Tobin adds, "I think one of the most powerful messages that kind of goes beyond the narrow group that we learned from and heard from is what does it mean for love to be politically and morally motivating? When we say we want to love people that are not in our families or our friends, like what does that mean, what does that look like? How can I engage in a love ethic and a love politics that's really aimed at justice? So anyone who cares about that question I think can learn something from the book, can learn something from their stories because they're trying to enact that and are having some success."

_