Milwaukee recently found itself on a list of 33 cities accused of concealing dangerous levels of lead in its drinking water. The Guardian claims the city’s testing methods are faulty because testers run faucets – or pre-flush a water system – before collecting the samples.

Milwaukee Water Commons' Ann Brummitt says her concern began to increase last January when she read an article in the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel about the potential threat of lead contamination and the cost of fixing the problem.

”[When I looked] at the Milwaukee Water Works website again, and I thought maybe after the Guardian article they would have changed this. But it still suggests that if individuals want to test their water. That they should collect a sample in one of two ways, let the tap run three to five minutes and then fill the sample bottle,” Brummitt says.

The Guardian article calls pre-flushing a way to cheat and conceal dangerous lead levels.

Director of disease control and environmental health with the Milwaukee health department, Paul Biedrzycki says, “I did look at the article and I think cheating would be fairly harsh.”

He blames flawed federal standards. “There are loopholes in the existing regulation that allow for compliance that may not be the veracity in terms of protecting public health,” Biedrzycki says.

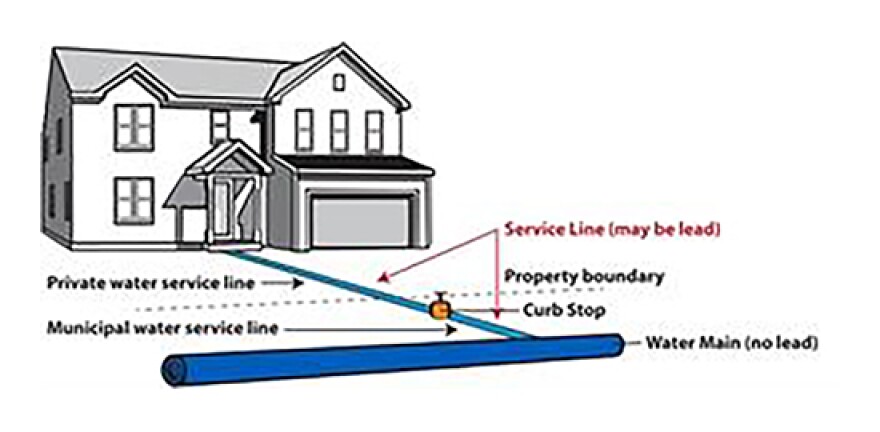

Milwaukee’s drinking water infrastructure amounts to mile after mile of mains– sort of the expressway delivering water to neighborhoods, which the city is responsible for.

Lateral pipes connect the main to houses. The city is responsible for the portion up to the property line. The property owner has to take care of the rest.

Approximately 70,000 properties in Milwaukee are at risk. They were built before 1951 when communities commonly installed lead pipes.

In 1996, Milwaukee took a step to keep the issue at bay. It started adding a phosphorous compound to its drinking water. The compound coats pipes to control lead corrosion.

Milwaukee has met federal regulations under the Lead and Copper Rules since 1999, so the city is required to test only 50 homes for lead, every three years.

Biedrzyski believes more comprehensive testing is needed – not only in homes but also in schools and day care centers. “We need to collect what we call first-draw samples to get a more accurate picture of the worst-case scenario and then we need to do laboratory analysis that considers total lead,” he says.

Ann Brummitt’s group – Milwaukee Water Commons – agrees, but is also calling for a comprehensive plan to replace the entire lateral system – both city and property owner sides. “Those 70,000 homes, this is an environmental justice issue as well. Any home built before 1950, you can’t be sure, but it maps onto some of the poorest zip codes in Milwaukee,” she says.

Mayor Tom Barrett insists the city is on top of the situation. He says, in 2015, a small sample - 6 households in Milwaukee - tested high for lead after the city replaced a water main and connected it to existing lead laterals.

“We made the decision that we were going to contact all of the dwellers to let them know if they were potentially affected,” Barrett says.

A few months later, the city sent letters to all residents living in older housing stock advising them to run their faucets for three to five minutes, if water has been sitting in the pipes for a while.

“So we sent that out in early February to the 70,000 dwellers. We made the decision based on six homes because we could see the evidence was pretty overwhelming, just in those six homes. So we will do more testing. But I’m not someone who is denying this is a problem. This is not like a climate change denier. We think there is an issue here and we want to address the issue,” he says.

Barrett says the city’s long-term goal is to replace lead laterals whenever a main breaks or is scheduled for replacement but he can’t promise the solutions will come easily or cheaply – particularly for the sections on private property.

“Under state law, we cannot use water utility resources. So the question is how do you pay for that portion and who pays for that portion,” he says.

Barrett expects the federal government to eventually require cities to replace lead water lines, in the meantime, “It is a test for us. If we’re the self-proclaimed experts on water and water technology we have to make sure we literally clean up our own back yard,” he says.