Update:

The last remaining child of Aldo Leopold died this week. Estella Leopold was 97.

Her father’s 1949 book, A Sand County Almanac , fueled the conservation movement. As an adult, Estella carried on the family tradition, as a paleoecologist and conservationist.

The Aldo Leopold Foundation says a tribute to Estella will be part of the Leopold Week kickoff at noon on Friday, March 1.

Original story from January 2, 2017:

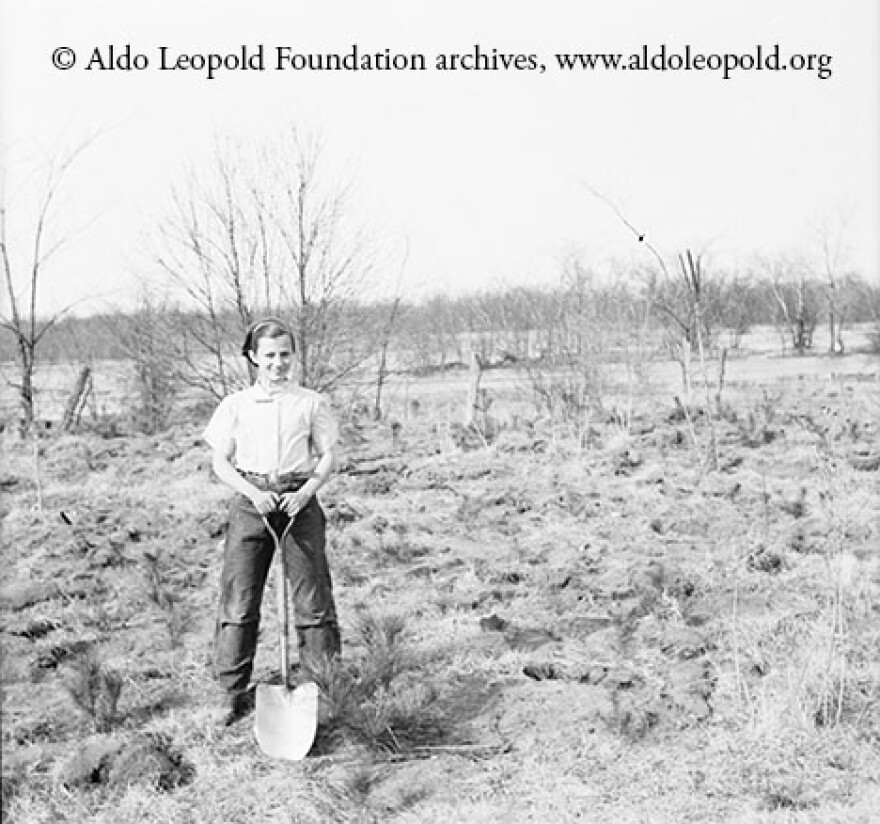

Aldo Leopold’s 1949 book A Sand County Almanac fueled the conservation movement. Estella Leopold, a vibrant nearly nonagenarian, was the youngest of five Leopolds. She grew up happily oblivious of her father’s fame.

Aldo was teaching at UW-Madison in the 1930s, when he bought a shack – quite literally, a ramshackle small barn – fifty miles to the north on what was exhausted farmland.

Estella loved the land.

“You get up on that hill and you walk above the shack and it’s a nice gentle slope and you get up on top, here’s this great big rock up there, which the glacier perched and then steep, it’ drops off into the woods,” she says.

She felt as passionate about the nearby Wisconsin River. “My cousin and I used to unload the car, asked if we could be excused and we would run down to the river and take all our clothes off and jump in the river and stay there until they called us home,” Estella said.

Her parents sounded a horn which hung inside the shack.

“Which they used for archery to call they would communicate together when they were hunting using this horn, which was a cow horn with a mouthpiece in it. That’s what we did,” Estella recalls.

She filled nearly 300 pages with memories and photographs in her recent book Stories from the Leopold Shack – Sand County Revisited, even including details of the cookware they used.

“There’s a drawing in the book of the lovely teakettle and then there’s the trivet that dad had made in Baraboo, it’s from little iron rods the size of your finger,” Estella says.

A blacksmith fashioned them into a tripod, which stayed next to the fireplace to keep dinner plates warm, the way her dad liked.

“That was a favorite! And then we had these white cups you’ll also see in that drawing, exactly like you can get in hardware stores today,” Estella adds, “I just love those, they’re so pretty.”

The Leopolds worked up healthy appetites. They not only shored up the shack, but planted countless trees. Estella wrote, "It was Dad’s idea that we should pay attention to the plants around us. We should seek out native species to bring to our land, plants that belonged in this part of Wisconsin.”

One day, the young Estella told her father she intended to become, in her words, a "bugologist." Over time, her course and location shifted.

“(I worked with the) Geological Survey in Denver and got a reputation there for being a paleontologist – fossil plants – and carried that to my work at the University of Washington and taught forestry and geology and botany,” Estella says.

The Leopold ethic of caring for the natural world seeped deep into all of Aldo’s children. The National Academy of Sciences recognized three of them for their research, Estella among them.

But she’d rather reflect on her parents. Her mother was a musician and wove music into her children’s lives. Estella says the family spent happy times singing together.

The Milwaukee Zoological Society’s Kohl’s Wild Theater is staging a production brimming over with music about the Leopold legacy targeting young audiences.

Coordinator Dave McLellan says Aldo Leopold and the Ghost of Sand County starts touring schools in southeastern Wisconsin this week.

"This show has Aldo Leopold and his three youngest children. Estella is the youngest, and she’s really the star of the show,” he adds, “ We hope that we’re empowering the children in the audience that they too can grow up to be amazing conservationists.”

McLellan says Estella Leopold’s book was a great resource. “And what’s really great is that Estella has had a chance to participate in the development of the piece,” he adds.

And participate Estella did. She received an early draft.

“When I started to read it, I wrote them immediately and told them I would never scold my dad for any reason, ever, I wish you’d take that out,” Estella says.

She may not know the ins and outs of the production, but believes wholeheartedly with its mission.

“You don’t have to have a lot of land; it can be a vacant lot, it could be a backyard, kids can enjoy simple things like that,” Estella says.

She knows firsthand the power of nature on a young child.

_