When Madison Memorial High School sophomore Demitrius Kigeya solves math problems in his head, other students give him surprised looks. He believes it is because he is black.

“I just pay attention in class and do my homework,” said Kigeya, 15.

Odoi Lassey, 16, a junior, echoed Kigeya’s feelings.

“People don’t expect you to know anything,” explained Lassey, who, like Kigeya, is a high academic performer, plays on the high school soccer team and is active in Memorial’s Black Student Union.

“It’s almost as if you know something, they think you’re weird or you’re acting white … some people think you’re not black just because you try to help yourself out and do well in school.”

The negative stereotype that follows students such as Kigeya and Lassey is rooted in Wisconsin’s dismal racial academic achievement record.

A Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism review of two decades of data pertaining to black-white academic disparities yielded few signs of progress. In fact, the gap has widened in some areas during that time.

Today, Wisconsin ranks the worst in the nation for:

- The difference between how well black and white students perform on a national benchmark test.

- The likelihood that black students will be suspended from school.

- The difference between black and white student graduation rates.

Wisconsin has been labeled one of the worst states in the nation for black children based on measures including poverty, single-parent households and math proficiency.

Tony Evers, the state superintendent of public instruction since 2009, conceded there is only one way to describe Wisconsin’s achievement gap: “It’s extraordinarily horrible.”

The gap, he said, has racial and economic causes.

“Wisconsin has a history of not being able to solve this issue and, frankly, not being able to lift people of color out of poverty in any significant way,” Evers said.

“Can we do more in our schools? Yes, and we should do more. But the fact of the matter is, we need the entire state to rally around people of poverty or this will never be solved in a satisfactory way.”

The struggles of Wisconsin’s black students are particularly stark, considering the state’s students as a whole perform at or above national averages on standardized tests, the class of 2014 graduated at the third-highest rate in the nation, and Wisconsin high schoolers are among the top scorers on the college aptitude ACT test.

It is not just that the state’s students on average perform so well. Wisconsin’s black students scored below the national average for black students in all four tested categories in 2015. For example, among fourth graders, Wisconsin’s black students scored 193 in reading compared to a national average among black students of 206.

The shortfalls in Wisconsin dramatize the failure of national efforts to raise achievement levels. Congress passed the No Child Left Behind Act in 2001 in an effort to close the achievement gap, placing great emphasis on standardized testing. However, Congress left the law behind after years of partisan bickering. President Barack Obama signed the changes into law Dec. 10.

The new law shifts more power to states and districts. States are still required to take steps to improve the lowest performing schools, but the bill does not mandate specific action if those goals are not met.

Evers said the bill provides an “opportune” time to discuss equity in schools.

“Allowing states to explore different methods, centered on their needs, to tackle achievement gaps will ensure that all students graduate ready for college and career,” he said in a statement.

Tests show lagging performance

Test results released in October from the 2015 National Assessment of Educational Progress, a set of tests known as the Nation’s Report Card, reaffirmed Wisconsin’s poor record of educating black children: The state had the worst achievement gap between black and white students in fourth- and eighth-grade reading and math. This is the second time in a row Wisconsin has been ranked the worst among the states assessed.

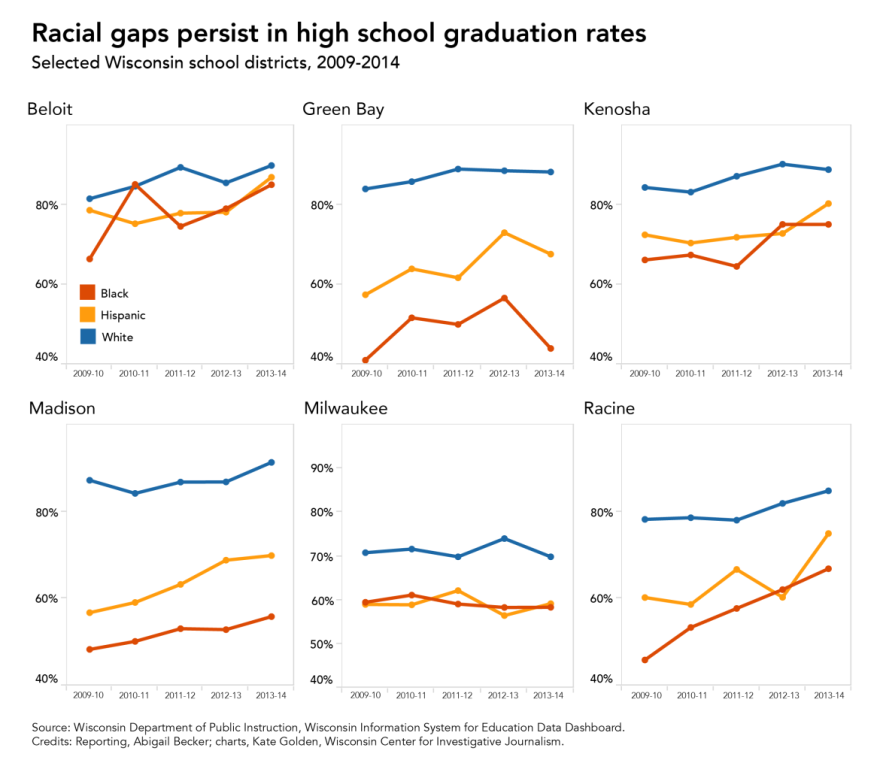

Wisconsin also has the biggest disparity in graduation rates between black and white students, according to preliminary data from the U.S. Department of Education. The rate for black students in Wisconsin held steady in 2013-14 at 66 percent, while the graduation rate for white students rose a half-point from just over 92 percent to just under 93 percent.

The causes of this gap are complex and extend beyond the four walls of a classroom, often preceding students’ first steps through the schoolhouse doors, researchers say. Factors include poverty and unemployment, historic discrimination, segregated schools and neighborhoods, racial bias and low expectations that damage students' motivation.

Fatoumata Ceesay, a freshman at the University of Wisconsin-Madison who attended Madison East High School, attributes her academic success to two college readiness programs, one through school and another that offers after-school and summer programming.

Ceesay, a student of color, said in her experience, students of color were not challenged in school and operated under low academic expectations.

“Usually students of color are dissuaded from trying so hard and that really, if you’re not encouraging someone, you’re going to give up eventually, which is what happens,” said Ceesay, an aspiring photojournalist planning to major in journalism and political science.

Wisconsin ‘worst’ for black children

Black students in Wisconsin are more likely to come to school hungry, abused or neglected — proven roadblocks to academic success. In fact, the 2014 Wisconsin Council on Children and Families report, Race for Results, labeled Wisconsin as the worst state for black children to live.

In a comparison of 46 states, Wisconsin’s black residents ranked as the worst in four of 12 indicators including delayed childbearing, young adults who are in school or working, children who live in two-parent households, and adults who have completed at least an associate’s degree, the report found.

As of 2014, 49 percent of Wisconsin’s black children were living in poverty, compared to 11 percent of white children, according to data compiled by the Annie E. Casey Foundation’s Kids Count project.

Wisconsin’s high suspension rate of black students is another barrier to their success in the classroom.

A report from the Civil Rights Project at the University of California-Los Angeles found that Wisconsin tops the nation in suspension rates, disciplining 34 percent of black high school students. The state has a 4 percent suspension rate for white students — the largest black-white discipline gap of all 50 states at the high school level, according to the report. Wisconsin’s suspension rate for black elementary students is the second-highest at 12 percent, the report found.

“If we ignore the discipline gap, we will be unable to close the achievement gap,” the report’s authors write.

Researchers and policymakers disagree about whether there have been successful efforts in Wisconsin to narrow the racial gap. UW-Madison education researcher Bradley Carl said he has yet to find any program “that has moved the needle on (the achievement gap)” in a big way.

University and state researchers will have the opportunity to find and analyze the practices across the state that are working to close the achievement gap with a $5.2 million U.S. Department of Education grant — the largest research collaboration yet between the Department of Public Instruction and UW-Madison.

Gap large at ‘microcosm’ school

Despite high achievers such as Kigeya and Lassey, a racial chasm in academic achievement persists at Madison Memorial High School. The school describes itself as a “microcosm” of Madison, drawing its students from neighborhoods ranging from subsidized apartments to upper-middle-class subdivisions. Just over half of its 1,917 students are white, 35 percent are low-income and nearly 20 percent are black.

In the 2013-14 school year, about 9 percent of Memorial’s black students tested proficient in math and 13 percent in reading, compared to 46 percent of white students in math and 51 percent in reading.

Black students in school districts from Madison to Milwaukee and Green Bay to Kenosha also graduate at much lower rates than their white peers. The graduation rates of black students in some districts such as Beloit and Racine have improved in recent years. But Green Bay saw a big drop in the graduation rate of its black students, from about 57 percent in 2012-13 to 44 percent in 2013-14.

There are places where black students are not so far behind. In the Beloit School District, 85 percent of black students graduate from high school, compared to 90 percent of whites.

There are other signs of positive movement in Wisconsin.

The statewide four-year graduation rate and the graduation rate among black students have both increased in recent years, although racial gaps are still striking. Across the state, the black student graduation rate rose from 61 percent in 2009-10 to 65 percent in the 2013-14 school year. White students’ graduation rate increased from 91 to 93 percent in that same time.

Disparity sparks public debate

Wisconsin’s achievement gap is on the public’s radar. Evers formed a statewide task force of educators and others to highlight schools that are closing the achievement gap. And Assembly Speaker Robin Vos, R-Rochester, has created a task force on urban education.

Evers’ Promoting Excellence for All task force identified 39 promising strategies in schools across the state to raise the achievement of low-performing students.

Gloria Ladson-Billings, a professor in UW-Madison’s School of Education said at a panel Nov. 5 sponsored by Madison’s Simpson Street Free Press that calling it a “nagging achievement gap” does not do it justice.

“We’re in crisis,” Ladson-Billings said. “It is not nagging, it is persistent, it is structural. We’re at a point where we cannot go failing another generation of people.”

Carl said the fact that there are so few programs in Wisconsin backed up by sufficient research “is pretty indicative of the problem.”

For their part, Memorial’s Black Student Union members said they are working to change how others perceive minority students at school and in the greater Madison community.

At a recent roundtable discussion on the achievement gap at Memorial, BSU members said a variety of factors may be at play: feeling disconnected from teachers, lack of encouragement at home and different learning styles that they say teachers are not accommodating.

Robert Bennett, a junior who wants to pursue college basketball and veterinary science in college, said self-motivation might help diminish negative stereotypes about black students.

“(Stereotypes will) still be there, but if the majority of people that are black start doing what the normal is — going to school, doing everything you have to do — then stereotypes will slowly start to go away.”

The nonprofit Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism (www.WisconsinWatch.org) collaborates with Wisconsin Public Radio, Wisconsin Public Television, other news media and the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. All works created, published, posted or disseminated by the Center do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates.