UPDATE: A Senate committee has approved the bill that would create a state-operated recovery high school in Wisconsin. The proposal calls for a pilot charter school program, that could open as early as the fall.

The matter moves next to a full vote on the Senate floor.

Original post: March 27, 2017

Think back to the challenges you faced as a teenager -- things like homework, hormones, peer pressure. These days, more teens than ever before have another concern tacked onto that list: addiction.

Young adults between 18 and 24 have some of the highest rates of substance abuse in the U.S. And with drug-related deaths reaching epidemic levels, many public health advocates say it’s time to find new ways to curb drug use among teens.

Like recovery schools – alternative programs for teens working to overcome addiction, while earning their high school diploma.

These schools combine education and therapy – and right now, there’s only one of them in Wisconsin.

An unorthodox program

Pulling up to the front door at Horizon High School, you might think you have the wrong address.

The school building is a strip mall, down the street from Target and Pick ’n Save, on the outskirts of Madison. Horizon shares a parking lot with a pizza parlor and a yoga studio.

And when you walk in -- no lockers, no hallways, even.

“It’s not really big,” says 14-year-old student Dez, as she leads me through a glass door to a conference-sized room. Student artwork covers the purple walls, with stacks of worksheets and various textbooks strewn across tables.

Within seconds, Dez gives me the tour. There are only four rooms. “Art, bathroom, kitchen, classroom,” she says, pointing out four separate corners of the large room.

It’s an unorthodox location. But then, so is the program.

"I think everyone's made stupid mistakes when they're a teenager that they regret, whether it's overdosing on drugs or having a stupid haircut."

In a lot of ways, the kids who attend Horizon are like their peers – but with one key difference. Students here are working through alcohol or substance abuse --- and in many cases, mental health issues.

“We’re just kids, we make stupid mistakes,” says 17-year-old student Ken. “I think everyone’s made stupid mistakes when they’re a teenager that they regret – whether it’s overdosing on drugs or having a stupid haircut. Every person is different on their issues.”

Like his Horizon classmates, Ken doesn’t go to a neighborhood high school because he’s struggling. He deals with severe depression, anxiety and a family history of drug abuse -- all factors that put him at high risk for developing substance issues. That’s why doctors referred him to Horizon.

“We’re all at our last point here,” Ken says of his classmates. “I think that’s what most recovery schools are – you’re at your last chance, for the most part.”

What's a day like?

Although this small Madison school might be a ‘last chance’ for these kids – who are referred to Horizon for help -- the environment is anything but doom-and-gloom. The kids smile, and crack jokes – they seem comfortable with each other and with the staff. There are only 15 students, along with one teacher and two teaching aides.

And no two days are ever the same. The school schedule varies from day to day -- but it always includes academic instruction and group therapy.

Kids here learn math, reading, science, social studies -- your typical high school subjects. But they plug into each subject where they can. They’re working on credit recovery – because, as Horizon’s director Traci Goll puts it, addiction doesn’t follow a traditional school calendar.

“We take kids any time of the year, and the minute they start at our school they start to earn credits,” Goll explains.

“Is that easy for the teacher? No,” she adds. “It’s so hard, because you’re constantly recreating the wheel. How are we going to get this kid with these math skills and these low reading scores to fit in with the whole group?”

The job of piecing that puzzle together falls to head teacher Ketrick Lehmen -- or ‘Ket,’ as the kids call him.

“We have ways of just sort of making sure everyone’s being taken care of,” Ket relays. “Maybe three different areas of a class are being taught at any given time.”

Senior Aaryn, 18, appreciates the individual attention she gets at Horizon. She feels like she’s learned more in a year and a half here, than she did at her former school.

“It’s not always easy! Don’t get me wrong. It’s definitely not easy” she chuckles. “But Ket has a way to like, explain it.”

"I want them to turn into mature adult people that make good decisions, that those critical thinking skills are gained from the education that they receive at Horizon."

Ket adds that he’s not as concerned with how the classroom might look or what kids know, as much as how they learn.

“I want them to turn into mature adult people that make good decisions, that those critical thinking skills are gained from the education that they receive at Horizon,” Ket says, “not necessarily, you know, a volume of facts that they retain.”

“It’s more critical thinking skills that can be applied to any situation in life. That’s the goal, and that’s what they need.”

Another thing Horizon students need that they can’t get in a traditional school setting: treatment.

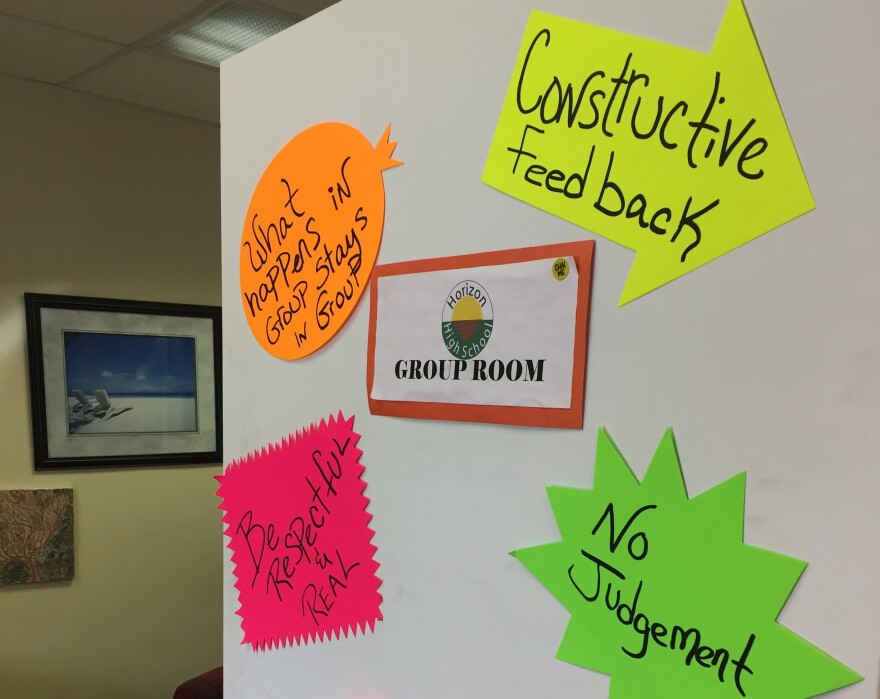

The Madison school carves out time for therapy every day. Certified counselors lead group and individual sessions to talk mental health, social life, family --anything going on in the kids’ lives that could impact their substance issues.

Student Ken says group is one of his favorite aspects of school at Horizon. “I’m struggling, but I’m not the only one,” he says. “I can look at others, and…we’re all struggling and we all care about each other. We kind of help each other out.”

And when they’re not in group therapy or working on their studies, students get to let off some steam. Once a week, Horizon staff take the students to a neighborhood health club. Sometimes, they’ll even get lunch at the nearby mall, as a special treat.

Director Traci Goll says she tries to incorporate the gym and similar field trips to teach the kids healthy habits -- “life skills,” she calls them.

“Do you feel like the mom in some of these situations?” I ask Goll.

“Oh yeah! They call me mom,” Goll laughs. “I had one call me ‘grandma,’ that really ticked me off!”

Goll says students in recovery have extra needs, so it takes extra attention and resources to get them through school. That often means extra money, too – something many recovery programs struggle to find.

Schools like Horizon are generally private programs. They rely on outside groups for funding, so budgets aren’t always stable. In fact, two former recovery programs in Wisconsin had to shut their doors because of funding issues.

To increase access for students, some state lawmakers hope to fund another recovery program like Horizon, among other initiatives to curb the state's growing opioid epidemic.

How much does a recovery school cost?

Money pays for things like drug tests – Horizon requires each student to take one random test per week, in order to stay enrolled.

Drug tests aren’t part of your “average” school day, but they are part of this program that has proven to work. Research shows kids in recovery schools like Horizon have better sobriety levels and better grades than students with addictions who remain in regular class settings.

“The kids that are in recovery schools tend to have needs in education, of course, but also in health & human services, for their substance use disorders,” says Dr. Paul Moberg, who studies recovery schools out of UW-Madison. “Many of them have concomitant mental health issues that need to be provided for. A lot of them also have issues with family relationships and dynamics, and maybe one-third or so are also involved in juvenile justice systems.”

Moberg points out that in addition to teachers and building costs, Horizon has to cover things such as drug tests, counselors and summer school -- so kids can continue to get the attention they need year-round.

As a private non-profit, Horizon contracts with local public school districts. When students are referred to Horizon, the money to educate them comes from their home district. But that amount only covers about one-quarter of the cost it takes to get each kid through Horizon. So, many of the schools Moberg has studied rely on fundraising and donations.

“The biggest problem has been to get them institutionalized in communities with stable funding streams,” he says. “There’s no mechanism to really braid those funding streams together to pay the full cost of what the kinds of programs that are being offered, cost.”

More often than not, recovery school leaders like Traci Goll have to cobble things together for their students. Goll is originally from the Madison area, where Horizon is located – so she knows a lot of folks who can help out. The day we visit, she’s thrilled to get a text from her friend who’s moving out of town – and offering the school furniture.

“I’ve never seen someone get so excited about chairs before,” says student Aaryn.

“Hey, this stuff is expensive!” Goll retorts with a smile, before she goes back to scrolling through the pictures on her phone.

Despite their limited budgets, programs like the one at Horizon have proven effective in helping kids curb drug and alcohol addictions – all while enabling them to earn their high school diploma. And those statistics have attracted legislators’ attention.

"I feel like every year at this job, I never know what’s going to happen next year."

As part of their efforts to curb opioid- and other drug-related deaths, Wisconsin lawmakers have proposed funding a state-run recovery school. Just like Horizon, it would educate up to 15 students. But the new school would get its money from the state budget. Lawmakers are also trying to work with insurance companies, to help cover the medical components necessary in a recovery school.

The idea has bipartisan support.

“This [has] now gotten to the level of being a public health crisis, and we’re losing too many young people,” says Democrat Christine Sinicki, who represents the southern suburbs of Milwaukee – the area with the highest rate of overdose deaths in the county. “We need to really start looking at creative ways to work with children who are addicted.”

Back at Horizon, Traci Goll likes the idea of a new state school, so more than the 15 students her school works with, could get the help they need. But, Goll has words of advice for whomever might end up running the state program: don’t get too comfortable.

Goll says the funding woes at Horizon keep her staff in limbo each semester. In fact, the school has been on the brink of shutting down several times – most recently, last spring.

“I feel like every year at this job, I never know what’s going to happen next year.”

Goll adds that she hopes to get the word out to more people about the value of programs like Horizon – and the need for more schools like it.