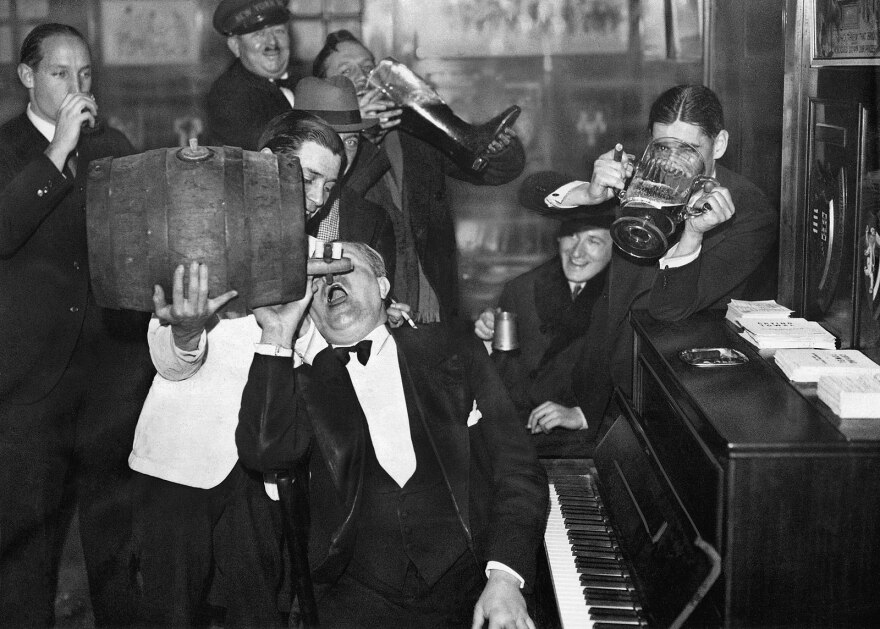

On January 20, 1920, prohibition became the law of the land in the United States and the production, transportation and sale of alcohol became illegal. Milwaukee is famous, or perhaps infamous, for its drinking culture so it can be difficult to imagine a Cream City without breweries or bars. But for many in Milwaukee, they didn’t let the 13-yearlong ban stop them from drinking.

Matthew Prigge is an author and historian from Milwaukee. He recently wrote a piecefor Milwaukee Magazine detailing what prohibition-era Milwaukee looked like and how residents avoided the law to continue consuming alcohol.

“People didn’t change their behaviors all that much, the transition from pre-prohibition to the prohibition period, as far as tavern culture was concerned really just involved a lot of, you know, shifting definitions of what a tavern was,” he says. “A lot of the bars that were operating in the city just never closed because there was not only the issue of people maybe not taking this seriously in the long-term but there was also the issue of enforcement.”

Prigge says city officials didn’t want to enforce the new constitutional amendment. That meant it fell on federal agents to track down bars illegally selling alcohol, but, he says, the prohibition office in southeast Wisconsin was understaffed and couldn’t pursue every speakeasy.

While taverns had to focus on avoiding federal agents to stay in business, breweries pivoted away from alcohol. Pabst turned to making cheese, others made non-alcoholic beer and Gettleman brewery started producing snow plows. Still, Prigge says in the beginning thousands of jobs in Milwaukee breweries were lost.

“They were the big businesses, they were, I don’t want to say prepared for this, but they were a little more equipped to take the hit than the local tavernkeepers,”he says

A new profession was created out of prohibition, those laid off brewery workers went to work helping people make their own alcohol at home. As stockpiles of pre-prohibition alcohol ran dry, more Milwaukeeans turned to trying their own hand at making a hard drink. Prigge says that malt and hops, two ingredients used to make beer, became difficult to purchase in Milwaukee because of the high demand from people brewing in their own homes.

“The public library had all of a sudden lost all of their copies of winemaking books from people just stealing them or checking them out and never returning them,” he says.

Despite the help from library books and former brewers, the alcohol people were making was not great and alcohol poisoning became even more prevalent.

Finally, after 13 long years, the 18th amendment was repealed on December 5, 1933. But on December 4, Prigge says federal agents did one last raid on a Milwaukee bar to seize illegal alcohol that would become legal the next day.

“[Raids] continued up until the very last hours, before the repeal of the 18th amendment went into effect. It must have been an odd time that they had to go in to bust up this place that if they just waited one extra day there would have been no violation there,” he says.