This weekend marks the 50th anniversary of the occupation of a Milwaukee coast guard station by members of the American Indian Movement.

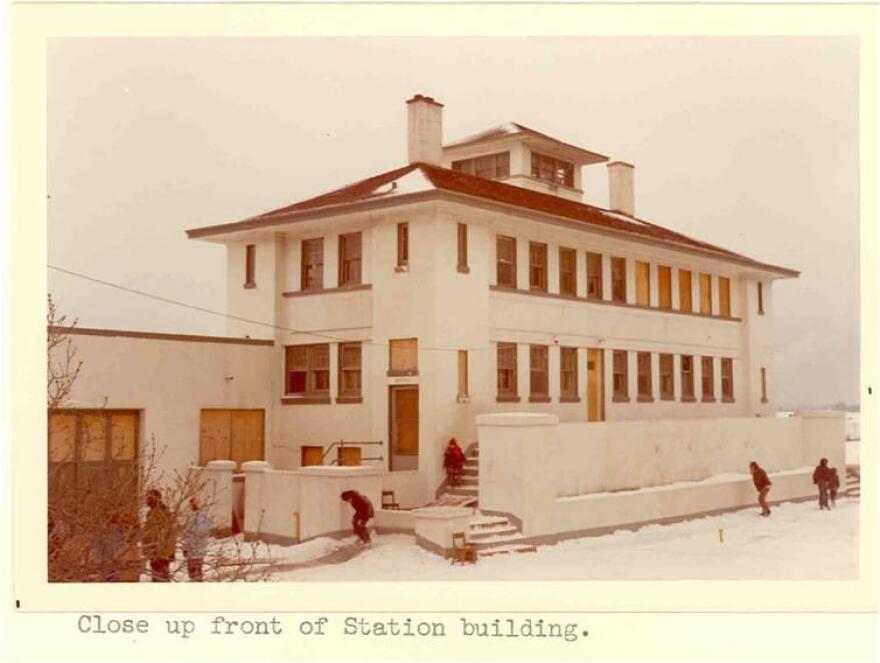

The Treaty of Fort Laramie of 1868 states that abandoned federal property should revert to the control of the original inhabitants. In the early morning of August 14, 1971, Herb Powless and local chapter members of the American Indian Movement took over the abandoned McKinley Coast Guard station along the Milwaukee lakefront in an effort to regain it from the federal government.

After a tireless summer, the land was returned back to the tribes of Wisconsin. Powless, the leader of the Milwaukee American Indian Movement Chapter, continued to advocate for health care, employment, cultural, and education support for Native Americans up until his death in 2018.

Dorothy Ninham was at the McKinley Coast Guard station takeover. Ninham is also a member of the American Indian Movement and was married to Powless. "You have to remember what the conditions were at that time...housing was very hard for Native people in Milwaukee, we were fighting for education, decent education, to get our kids in quality schools, we were fighting for employment. In addition to all of that we were fighting alcohol and drug abuse in our community." Ninham remembers.

The celebration is set to take place August 15th at 1:00 p.m. at McKinley park. The event will host a myriad of guests and performances including Bill Means, the co-founder of the International Indian Treaty Office, as well as Purple Chuck, a young Native American rapper.

"It’s a tribute to what can happen when Native minds are put together and we work for something positive," Ninham acknowledges. "We’re thinking about the next seven generations, so I think it’s really important to celebrate what we’re really capable of and who we are."

Read the full transcript of Lake Effect's Mallory Cheng conversation with Dorothy Ninham and Perry Muckerheide here:

Audrey Nowakowski: This is Lake Effect from 89.7 WUWM, Milwaukee's NPR. I'm Audrey Nowakowski. Thanks for joining us. We'll start with this. The Treaty of Fort Laramie of 1868 stated that abandoned federal property should revert to the control of the original inhabitants. In the early morning of August 14, 1971, Herb Powless and local chapter members of the American Indian Movement took over an abandoned McKinley Coast Guard Station along Milwaukee's lakefront. After a tireless summer, the U.S. federal government returned the land back to the tribes of Wisconsin. Powless, the leader of the Milwaukee American Indian Movement chapter, continued to advocate for health care, employment, cultural and education support for Native Americans up until his death in 2018. Dorothy Ninham was at the McKinley Coast Guard Station takeover and is a member of the American Indian Movement and was married to Powless. Perry Muckerheide is a coordinator of the Coast Guard takeover 50th anniversary celebration. They spoke with Lake Effect's Mallory Cheng, about the long standing impact of the movement's activism and advocacy.

Mallory Cheng: Dorothy, take me back 50 years to August 14, 1971. You and your husband, Herb Powless, led a group to take back the old Coast Guard Station right off the lakefront. Why that station and what was running through your mind at that time?

Dorothy Ninham: Well, I think that that was 50 years ago. And you have to remember what the conditions were at that time. There was... housing was very hard for Native people in Milwaukee. We were fighting for education, decent education, to get our kids in quality schools. We were fighting for employment. In addition to all of that we were fighting alcohol and drug abuse in our community. And so our minds were on getting a better life for our people, and trying to be good examples to lead the struggle for treaty rights. Why the Coast Guard Station is because it was abandoned federal property. And according to our treaty rights, the land is supposed to be turned back over to the tribe, instead of being sold or...or anything else we know whenever there is abandoned federal property, it's supposed to revert back to the tribe. So we were trying to bring attention to that because nobody was paying any attention to the treaty rights, or the sovereignty of Native American people.

Cheng: And what was running through your mind at...on that night, on the early morning of August 14?

Ninham: Well, on that night, you know, nobody really knew what was going to happen. Anything could have happened. And there weren't 30 people that went in with him, there were only seven people that went in with Herb. And I wasn't one of them. I didn't come in until in the morning. But they went in down there. And I got a call probably about five o'clock in the morning, saying they were in and that I could come down there. And I did go down there with my children. And we occupied the space. And I think that what was going through my mind was this is this is going to be a good day for Indian people. You know, we are trying to reclaim our land. And we're trying to do it in a...in a peaceful way. But also, you know, we had the law on our side. Treaty rights, are...treaties are the law of the land. And they were just a matter of making the government understand that.

Cheng: How long was the takeover? And during your time there did you experience any confrontation from law enforcement at all?

Ninham: Yeah, the police came down there. And there was, you know, there was a lot of confusion about what was going on as far as what we were doing. But I think pretty much they just let kept hands off and Herb went into D.C. right away and met with Brad Patterson. And got an agreement with them for us to keep that land. So when he went in, we just fenced it off and said, this is an Indian Reservation. Now it's back to Indian people. And if they were going to do anything, it would've have had to been federal officers coming in not state or local or county. I think they thought it was going to be a novelty, or maybe we get tired of it. But we occupied it for quite a while. We were down there during the summer. And you know, like a lot of different tribal people came down there and joined us and just enjoyed the camaraderie of everybody being together. And the first time that we were able to hold the land and say, "You know what, this is ours".

Cheng: The impact of the takeover is definitely long standing within the city of Milwaukee. How long exactly did it take for those changes to happen?

Ninham: The changes didn't happen immediately. And we worked, well Herb did. He went to D.C. and he worked with the officials there, you know, in reclaiming this. And he had Brad Patterson, who was a...who's a special assistant to President Nixon at that time on Native Affairs and he kind of took a liking, I guess, to Herb and our — if he didn't, he kind of knew what we were trying to do and, and worked with us to help it happen. And so it didn't happen immediately. But I know that we invited the Indian Community School to come down there and, you know, take a place in one of the buildings. We had an Indian halfway house that we had for recovering alcoholics, like a sober house. You know, that we had on the property that we made one of the buildings into. Once we, you know, we transferred the land to the school, let the school takeover on the Coast Guard Station site, we never let go of it completely. But we, we allowed the school to, to use that property and to...and they eventually we ended trading it up for an inner city school and they they kept trading it up until they got to where they are now, you know. They were able to buy the buy the land and put a big state of the art school on the land. And you know, it's just the culture is being taught down there. The languages are being taught down there. It's just amazing, you know, what the progress that of that has come from it. You have to remember that a lot of our people were moved from reservations, and put into the urban settings, and promised housing and employment and education. And a lot of that never happened. You know, some of these people ended up in worse conditions than they were on the reservations. You know, living in poverty, and some of them being homeless, and with, you know, like jobs that couldn't support a family. So it was it was really a tough time. It was it was tough for us, but we have to stand our ground.

Cheng: Dorothy, I just want to ask too...reflecting on the last 50 years since the Coast Guard takeover happened, what would you have told yourself knowing what you know now about where we're at, and what the impact of this event has been?

Ninham: What would I say to myself? I would have said keep on fighting. You know, the generations that are coming are worth it. You know, we need to get our traditions back. We need to get our culture. So much of that has been lost or just set aside just trying to survive. Those struggles was worth everything. Because we went... we were able to go back home. And right now I have a teepee in my backyard. I have a sweat lodge right near me. There's everything that we ever wanted is right here. You know, I would have said fight even harder.

Cheng: What can people expect to see an experience at that upcoming 50th anniversary event?

Ninham: We're having Bill Means who is a co-founder of the International Indian Treaty Office come in and speak. He's a great speaker and he can speak to a lot of the issues that the American Indian Movement has dealt with. I've also invited John Thomas, who is Pawnee from Oklahoma. He's out in New York and Pennsylvania right now dealing with the return of the bones of some of our people that were...that died while there were in boarding schools across the country. We're also going to bring in some smoke dancers from Oneida, a group of young guys that are into the traditional Iroquois style of dancing. we're bringing the Buggin Malone who is also Oneida and Potawatomi. And I believe part Ho Chunk. He is going to be coming in, he's young rapper who rapped native songs. The part about Buggin Malone coming in, is his mother was a part of the Coast Guard Station takeover. And her two brothers, Mike Denny, and Jack Denny were with Heb when they went in on the morning of the 14th. So it's really to me, it's really great to be able to bring him in and honor his mother, because she was so much a part of the struggle. And he's always been involved in fighting for sovereignty and fighting for native rights. So it's only just and fair that we bring him in too. There are so many native artists that I wish we had the opportunity to bring in, to showcase. We just don't have the financial ability to do all of that. I don't want it to come off as a tribute to either Herb or myself. It's, it's a tribute to the that what can happen when Native minds are put together and we work for something positive. We're thinking about the next seven generations. So I think that it's really important to celebrate what we are capable of and who we are. When I lived in Milwaukee, you have confrontations with different people and for someone to tell me go back to where you came from. That's exactly what I did. I went back to our roots, you know. Went back to the sweat lodge, went back to the the teepees back to our traditional ways. And, and that's how I raised my children. So it's kind of funny when people say go back where you came from. I'm more than happy to.

Perry Muckerheide: What's important is Dorothy is returning to the original site of the Coast Guard Station. It's no longer there it was it finally was taken down in 2008. There's a wonderful circular plaza that is dedicated to Charles Chuck Ward, who was a civil servant and ultimately administrator of the parks. It's right near the water inlet where the where the marina is now. So it's very easy to find. We are bringing a stage and a PA and Dorothy has invited friends in to, to speak and to sing and to dance, everyone is invited to come and show their solidarity with Dorothy and with the Indians, and really celebrate and commemorate everything that happened 50 years ago, and everything that came from it, talking about people who were at the occupation. One of the groups that did help us was the Forest County Potawatomi Community Foundation. And that's headed up by a wonderful woman named Kate Garcia. And while we were working on this, she told me that her brother and sisters actually went to school at the Indian Community School while it was at the Coast Guard Station. And subsequently, her aunt is the woman who, who organized the the school acquiring and moving into Concordia, before they moved on to their suburban location, now, all with the help of the Potawatomi.

Ninham: We've been fighting for the injustice of American Native American people, all these years. I mean, there's, if you look around there, you know, look at the statistics, there are more Native Americans that are incarcerated, per capita across the country than any other race of people. And I just wanted to say that we were targeted, you know, we were targeted once we formed the American Indian Movement, we were targeted and called terrorists, and everything else. And there are people who have paid the price or people who have died. Because of what we believe in. There are people who are still in prison, because of fighting for what we believe in. And the one that I want to mention, is Leonard Peltier who is still serving time in a federal prison in Florida, because of his involvement in fighting for sovereignty and fighting for, you know, for tribal rights. So that we have a long way to go, we are nowhere near the end of the fights, the end of the struggle, we got a long way to go. And we've got some good people coming up. You know, we still need people to get involved. We need people to, you know, to talk up for sovereignty and talk for rights whenever you can, because it just is, is such a system out there that it's so hard to get around, hard to understand. You know, it's hard to understand that, that we're being judged by the color of our skin. You know, we are all one people even though we are red, yellow, black and white. We make the circle together. We are all in this together. There is one earth for us to live on. We need to take care of our Mother Earth, and the water that my children drink that's being polluted by the oil spills. And by the drilling. You know, everyone else's children is going to be using that same water. So we need to remember how to live together in harmony and for what is right.

Cheng: Thank you, both of you for being here on Lake Effect today.

Ninham: You're welcome.

Nowakowski: Dorothy Ninham is a member of the American Indian Movement and Perry Muckerheide is a coordinator of the 50th anniversary celebration. They spoke with Lake Effect's Mallory Cheng and you can learn more about the 50th anniversary celebration happening this Sunday at WUWM.com