On Nov. 2, a team of divers and archaeologists carefully removed a 1,200-year-old dugout canoe from the bottom of Lake Mendota in Madison, Wisconsin.

The extracted canoe is made of white oak, and it’s the oldest completely intact canoe found in Wisconsin's history. Researchers hope the discovery will help them learn more about the way the state’s early Native American communities fished and traveled.

Wisconsin Historical Society maritime archaeologist Tamara Thomsen first discovered the canoe 27 feet underwater in June when she was out for a leisurely dive.

"I’ve seen a lot of dugout canoes being a maritime archeologist, not underwater of course ... and I looked at it kind of strangely ... [and] made a note of where it was," she says.

After returning to the site to take pictures and consult with another archeologist, they confirmed it was indeed an artifact. Thomsen also found rocks sitting at the center of the canoe that were used as sinkers to weigh down fishing nets.

"We don't know who was in the canoe, but 1,200 years ago it was the Effigy Mound period in Southern Wisconsin. And in particular on Lake Mendota and the Four Lakes areas here by Madison, it was a very active time, a very interesting time, a time when there was a lot of ritual activity on the shoreline," explains Wisconsin state archeologist James Skibo.

The Ho Chunk and Menomonee people have records of living in this area during this period, but with more study Skibo hopes to examine the stylistic differences of canoes and link the newly discovered artifact to a specific tribe.

Archeologists rarely find whole objects, and most of what they find are inorganic objects that people have thrown away, says Skibo.

"To find something that organic is rare. And to find something that is wood like this is rare. To find it being completely intact is extremely rare."James Skibo, Wisconsin state archeologist

Skibo admits he was skeptical at first that they had found an artifact that was so old in freshwater. However, a carbon date confirmed its age, launching a pressing timeline to extract the canoe.

"If something's going to survive that way, it has to be constantly wet, constantly without light, so it must've been buried so living organisms can't eat at it," Skibo explains. "And oak is actually a very strong, stable wood, and also the fact that it had interior charring, I think leads to its pristine condition."

Once the Wisconsin Historical Society decided to make a plan to extract the canoe, Skibo says that all of the local tribes were contacted. "They were part of this process as much as they wanted to be, and they will continue to be a part of the process as we move forward through interpretation and study of the canoe," Skibo says.

Thomsen notes that their office had never done any kind of excavation of this scale underwater, and making a plan to safely remove the canoe was "a learning process."

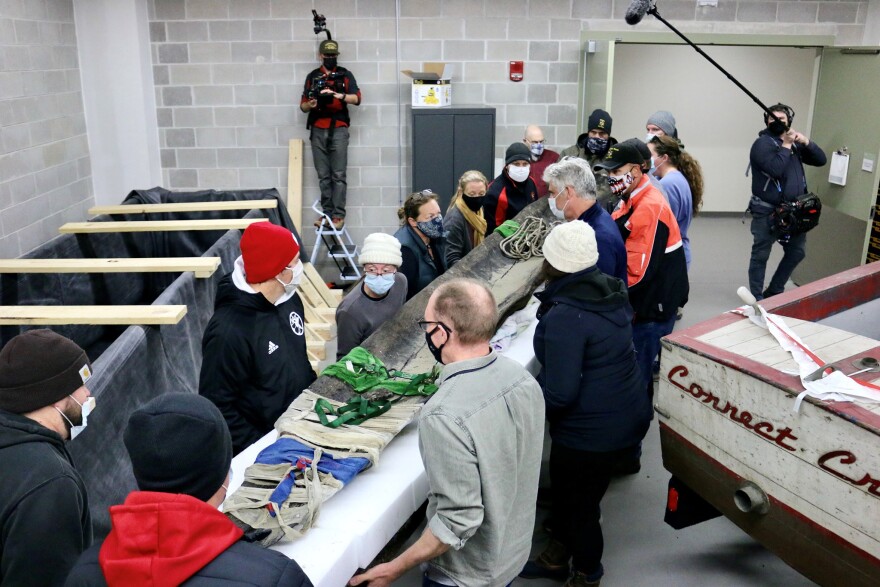

The first step in extracting the canoe was to remove the surrounding sediment carefully with a water dredge pump. According to Thomsen, this step also ensured no other artifacts were left on the bottom. Then, a water jet was used to cut underneath the canoe to free it from the hard clay at the bottom of the lake that held the artifact in place. A team of divers then secured the canoe with rebar and rope to ensure it wouldn't float away until they could return with the whole lift team.

Thomsen notes that divers from the Dane County Sheriff's Department also assisted with the extraction. Lift bags and a lifting hammock were used to bring the canoe to the lake's surface carefully. "We turned it sideways to the slope and put a little bit of gas into the lift bags. But basically, we swam it to the surface so that it wouldn't create pressure on sort of the cupped nature of the canoe and crack it open that way like an egg," explains Thomsen.

The canoe was supported on the surface with the rest of the lift bags and the team slowly towed the canoe to the beach and moved it to a new location.

Skibo says the canoe is currently stored in a specially made vat of tap water, and chemicals have been added to remove any living organisms that may still be in the water or canoe. It will stay this way until they start the preservation process, which involves gradually introducing polyethylene glycol to enter the cellular structure of the wood to help stabilize the object. This process can take up to two and a half years.

"The primary thing that's holding this canoe together is the water inside that's supporting it," notes Skibo. "In order for it to be preserved, we have to replace that water with something else." After the polyethylene glycol process is done, the canoe will be freeze-dried at -42 F to remove the rest of the water. It can then be moved safely, studied, and displayed without fear of it breaking.

Skibo hopes further study of the canoe will reveal more insights about subsistence, fishing, transportation and technology used in the Effigy Mound period.

Not only is the dugout canoe the oldest found in Wisconsin, but it's also the only canoe that had artifacts in it. The seven rocks in the canoe that served as net sinkers is the only clear evidence that this boat was specifically used for fishing. Skibo notes that most fishing canoes were intentionally placed at the bottom of a lake for seasonal movements, but the fact that it was found so far away from the shore intrigued them.

"It's likely that this canoe actually sank, so it's Wisconsin's oldest shipwreck," Skibo says.

Thomsen says the significance of her discovery and the extraction hasn't quite hit her. "I spent weeks and nights just worrying that I was going to damage this precious thing ... So it hasn't sunk in how important this find was, but it's definitely one of the better days at work."

For Skibo, discovering an artifact in public view made this it personally significant. "We get kind of jaded in our jobs, but when people can participate in something like that, be a part of it [and] see something that no one's seen for 1200 years, it was a moving experience for them, and their reaction moved me," Skibo says.