San Francisco has seen protests against the Google bus — private buses that carry tech workers to and from the city. Now there's another transit fight, this time over parking.

A few tech entrepreneurs are helping to sell public parking spots, even auctioning them off to the highest bidder. The city's attorney says that's illegal. The app makers are not backing down.

Mobile SolutionsTo TheParking Problem

Cruise around the Mission District in San Francisco, and between the storefront churches, the trendy new restaurants and the people moving in and out, it can be really hard to find a parking spot.

"I've spent as much as 45 minutes to an hour looking for spots," Robert Aparicio says.

Carol Scanlon says, "Usually during the day, the construction workers take all of the day spots."

Sean Carroll admits his pickup is parked illegally in front of a garage. "There's not an available spot, and we had a mattress in the back," he says.

These are familiar problems. And now, a handful of technology startups have come up with novel solutions: mobile apps that let people occupying public, metered parking spots sell to those without.

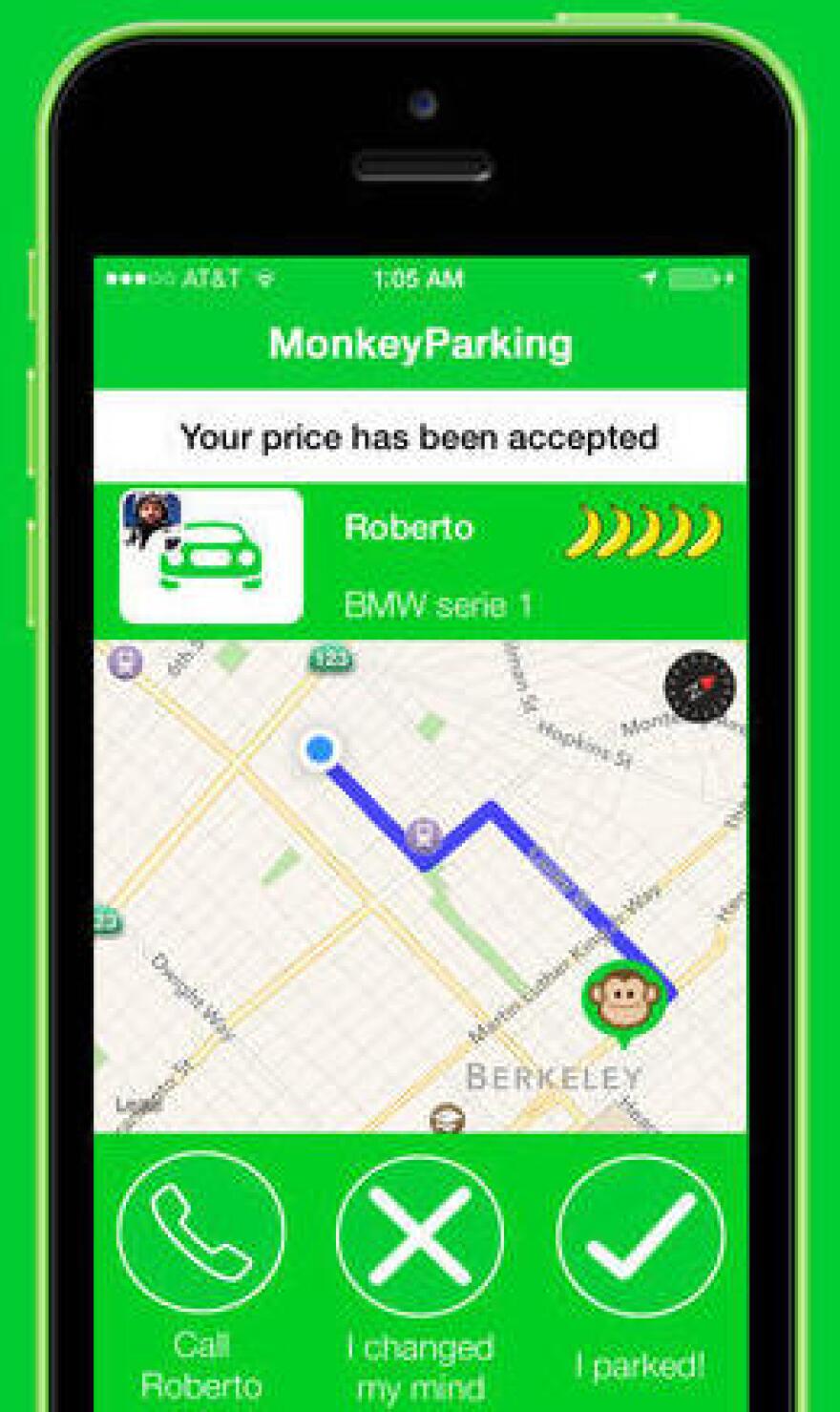

The apps come in different configurations. MonkeyParking lets you auction a spot, and founder Paolo Dobrowolny says you can make up to $150 a month doing it. "I have the right to tell when I am about to leave from a parking spot," he says. "And I have the right to be paid for giving this information to someone who wants it."

In theory, there is no limit to the price. But in practice, says Dobrowolny, $15 is the highest price that has been paid.

The app Sweetch sets a fixed price at $5. "It's the minimum amount of money that makes people collaborate together to help each other," founder Thomas Cottin says.

ParkModo, which is planning to launch, lets the person with the parking spot set the price. If you know you're leaving the dinner party at 10 p.m., you decide what that information is worth. "Under the terms of service, you don't have to wait for the next guy," says founder Daniel Shifrin. "Now if someone wants to sit in their car, I can't control that."

CeaseAndDesist

Parking apps are a new offering in the sharing economy. But unlike services that connect homeowners and car owners to online customers, these apps are built on a public resource. Before they get too popular, the city of San Francisco wants to shut them down.

"San Francisco's police code already prohibits anybody from buying or selling or renting on-street parking," says Matt Dorsey, spokesman for the San Francisco City Attorney's Office. "There's really no gray area here. It was illegal before the Internet, and it's illegal after the Internet."

The city recently served a cease and desist letter to MonkeyParking and plans to serve the other parking app services shortly. Drivers using the parking apps could be fined $300 per parking violation, under a 1980s statute.

Dorsey says these apps are a public safety hazard, encouraging people to stare at their phone while driving — and they're plain unfair.

Say a blue-collar worker is late for a date and he spots a highly desirable parking spot. "But somebody is holding it hostage while somebody with a lot of wealth can outbid [him] for it," Dorsey says. "That's not what on-the-street public parking is supposed to be about."

Selling Public Utilities

Arun Sundararajan, an economist at New York University, says the city of San Francisco is wrong. "The idea that things are built on top of government infrastructure or are taking advantage of public resources for profit isn't anything new," he says. "A lot of the capitalist economy is built on government infrastructure."

Telephone carriers and private garages build their businesses on top of public resources. If a mobile app can efficiently transfer something as small as a parking spot, Sundararajan says, that's innovation.

Price is a separate issue. In much of the sharing economy, services drive down the price. Airbnb is cheaper than Hilton. Zipcar for an hour is cheaper than Hertz for a day. But there's no rule in sharing that forbids variable pricing, scalping or bidding wars.

"It's not always going to be the case that prices are going to go down," Sundararajan says. "I don't think we should be surprised if the sharing economy marketplaces do in fact lead to higher prices for certain things."

'I Don't Care About Your App!'

At least in the short term, the parking apps could become yet another flashpoint in the ongoing tensions between old and new San Francisco.

Car owner Aparicio, who is a city native, says he doesn't pass up a parking spot when a guy is standing in it, trying to hold it. He is not going to defer to an app.

"Some tech guys tells me, 'But dude, I got an app that says so,' " he says. "I don't care about your app! This is city property."

The city says it has asked Apple to remove MonkeyParking from the App Store. But the app remains available, and Apple did not respond to NPR's media inquiry.

Meanwhile, MonkeyParking says it won't shut down because it's not selling parking. The app is helping people share information about spots and decide what that information is worth, the company says.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAxODc1ODA5MDEyMjg1MDYxNTFiZTgwZg004))