In the last decade, Erika Rosales has spent a lot of time worrying about how legal challenges to DACA will disrupt her life. The last few months waiting for the latest news on the program’s status were no different.

Rosales directs the Center for DREAMers at UW-Madison, which supports students with DACA across Wisconsin, providing services like legal advice, career coaching, and help with their DACA applications. She’s also a recipient herself, so dealing with the program’s ups and downs is difficult — personally and professionally.

“It never gets any easier,” Rosales said.

Since its creation in 2012, DACA — short for Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals — has protected hundreds of thousands of undocumented immigrants brought to the U.S. as children from deportation, including around 6,500 in Wisconsin today. They came from many countries, including Mexico, El Salvador, Guatemala, and South Korea.

The program opened many doors for this generation, known as the Dreamers, for the DREAM Act, which would have provided permanent protection for them but ultimately failed to pass in Congress. DACA status allows recipients to work, as well as obtain social security numbers and driver's licenses, in some states.

But DACA’s protection is limited — it comes in two-year, renewable increments — and the program is on shaky legal ground. With all the legal challenges over the years, including former President Trump’s attempt to revoke the program in 2017, one of the most reliable things about DACA has been its uncertainty.

In the latest of those challenges, last week, a federal appeals court ruled that DACA is illegal.

The 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals kept the program running — for now. That means about 600,000 people like Rosales can keep renewing their status. But many Dreamers are shut out of applying for the first time, while the lawsuit goes unresolved. There are currently around 1.3 million people eligible across the country.

“This decision is honestly not surprising,” Rosales said. “But it’s overwhelming in the sense that it continues to reaffirm the burden that we have to carry.”

The ruling upheld a decision from last summer, on a suit that Texas and eight other states brought against DACA in 2018. Last June, a Texas-based district judge ruled that the program was illegally created when former President Obama established it through executive action, rather than going through Congress.

The Biden administration appealed that decision. Then, in late August, President Biden tried to protect the program with a so-called final rule, making DACA law. Still, those efforts were met with disappointment from immigrant advocates, who said Biden’s rule took a conservative path in not expanding DACA, falling far short of the needed protections.

The latest decision sends the case back to the lower district court, with instructions to look at Biden’s new rule, which goes into effect on Oct. 31.

“DACA is not sustainable protection," Rosales said. “Even though it remains for now, it continues to be in danger."

Advocates worry the ongoing battle will wind up at the Supreme Court.

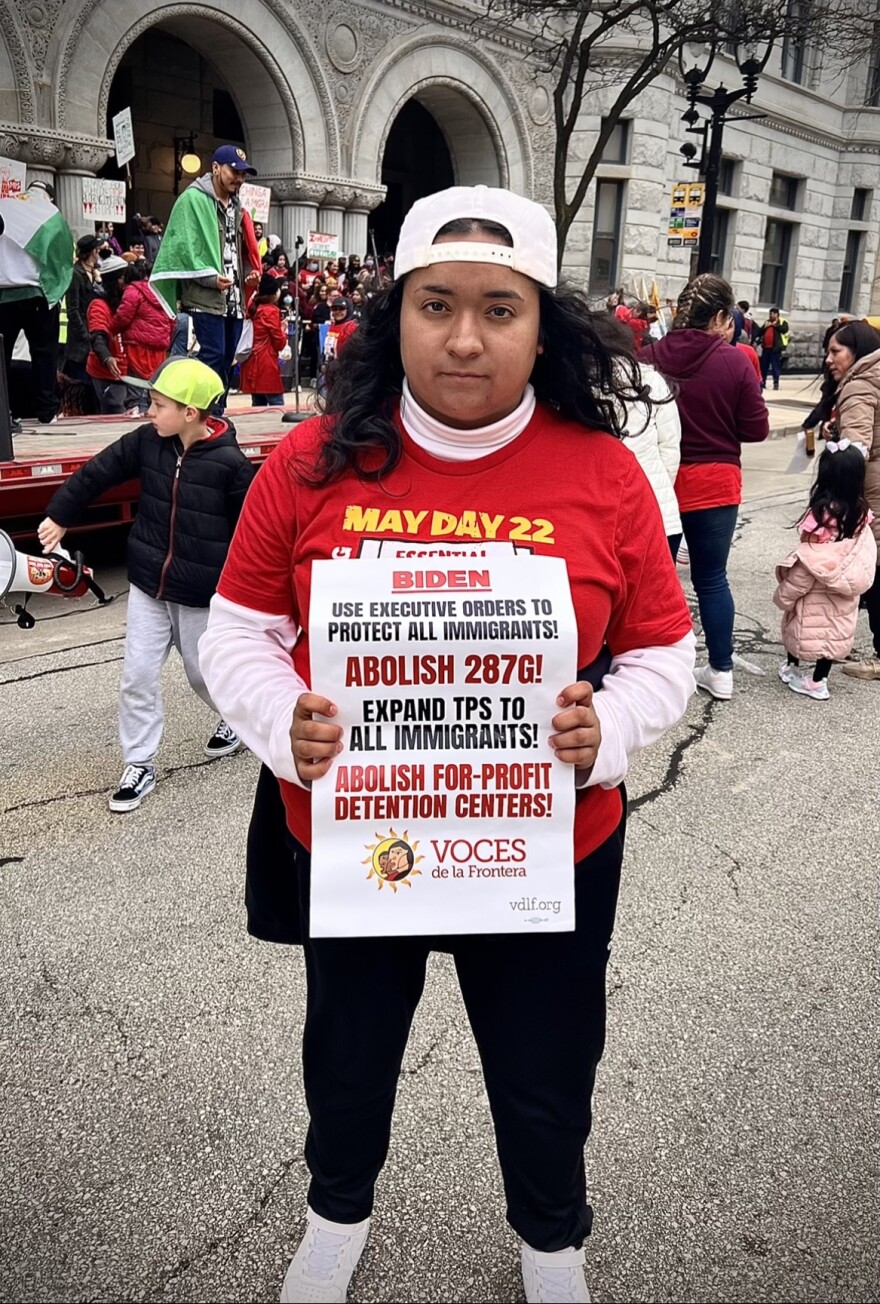

“If appealed — which it probably would be appealed — it would go to the Supreme Court,” said Christine Neumann-Ortiz, executive director of Voces de La Frontera, a Milwaukee-based immigrant rights organization. “Given the very conservative nature of the Supreme Court, it will likely pull the protected status that [recipients] have had for the last 10 years.”

That would affect millions of people — not just DACA recipients, but their friends, family, neighbors, and coworkers.

“Their lives are in play,” Neumann-Ortiz said. “People who’ve had the opportunity to build a life and help their family and live without the fear of deportation — that could dramatically change.”

DACA recipients are a huge force in the economy. In Wisconsin, they pay nearly $16 million in taxes, and work essential jobs across agriculture, healthcare, and education. For many, Wisconsin is the only home they've ever known.

Alondra Garcia is one of those people. In 1999, she moved to Milwaukee’s South side from Michoacán, Mexico, when she was a child. Today, she’s a bilingual teacher at Allen-Field Elementary School.

When DACA was first announced, Garcia was a sophomore in high school. Her father told her they would help her apply right away. He believed it would make life better for her, she said.

Garcia’s DACA status came with more responsibility at a young age. In Wisconsin, undocumented people aren’t permitted to obtain driver's licenses. Garcia was the first in her family to get a license, and her mother relied on her for rides to work.

Eventually, through her DACA status, Garcia went to college, kicked off a career in education, and helped provide stability for her parents and two younger sisters. She said DACA has let her live her own American dream — but a limited one, clouded with an uncertain future.

“I see my parents struggle in $15-an-hour jobs, and see that they’re still in the same situation,” Garcia said. “I’m in a better situation because I went to college, got a degree, and got a job that lets me live a pretty good life so far.”

Her achievements have come at great expense. The DACA application costs $495, a fee that’s required with every renewal.

“It’s painful to pay for that,” said Garcia, who has renewed her status five times now.

Undocumented students aren’t eligible for federal financial aid, and in Wisconsin, they must pay steep out-of-state tuition.

That’s why Garcia ended up attending a private college: They offered more financial support than Wisconsin state schools did at the time. Still, Garcia worked multiple jobs — as a tutor, babysitter, and cafeteria assistant — to fund her education and DACA fees.

Legal battles aside, there’s also the sheer anxiety of living life two years at a time. Planning for the future is difficult, said Garcia, who dreams of one day going to grad school and becoming a school administrator.

“I want to get there but having DACA’s not going to allow me to easily get there,” she said. She imagined getting halfway through a master’s program only to lose her status. “Having to work towards it, with all these fears, knowing that it can go poof.”

Advocates have long called upon Congress to create permanent protection for undocumented immigrants and a pathway to citizenship. But the government has so far failed to pass immigration reform.

“We need a permanent solution now,” Garcia said. “It’s time. It’s long overdue.”

Garcia said it starts with local elections, like the upcoming midterms. As a "DACAmented" citizen, she can’t vote, so those who can, she said, need to turn out and elect lawmakers who will support the immigrant community.