A national study of concussions suffered by football players and military cadets will move into a second phase, with the Medical College of Wisconsin continuing to play a major role. Findings from part one of the massive study appear to have brought some safety improvements to football. But the new round of research could bring more changes.

While football remains popular with millions in Wisconsin and the U.S, there are enough injuries that a pre-game prayer is said for the players at some venues.

"We pray that the players today remain free of injury and that they play the game to the best of their ability," said Rev. Kevin Voss of Concordia University Wisconsin, just before the Mequon school’s recent game with Wisconsin Lutheran College.

When the contest got underway, the two small college teams did not play at the speed or with the size of the Green Packers or the Wisconsin Badgers. But there was still plenty of firm blocking and tackling.

It was the last game of the year for both teams. Throughout the season, Concordia says there were a handful of concussions.

A concussion — where the brain bangs around inside of the skull — is a serious matter and something football teams didn't always seem to recognize or maybe admit. About 25 years ago, the National Football League set up a committee to look into head injuries. But the panel just issued a series of reports that played down the risk. Only in the last five years, has the NFL seemed to take concussions more seriously, partly pushed to do so through lawsuits and greater media attention.

Concordia's Sports Medicine Director Angela Steffen says she's seen a change in how injured players are handled at her school.

"Ten years ago, if someone got a concussion, we removed them from the field, but we sent them to class. Five years ago, we removed them from the field and told them to do nothing. Go sit, rest. Stay quiet. Don't exercise," Steffen told WUWM.

But Steffen says it was discovered that completely shutting down a high-energy athlete harmed their social well-being and ability to heal from symptoms like headaches and impaired mental skills. Instead, she says concussed players are now assigned limited exercise.

“Some light biking, walking, just getting the heart rate up a little bit. We're doing that two to three days in when they're still symptomatic. But what the literature is finding is, it's helping," Steffen said.

She says ultimately, those concussed players who exercise are able to return to normal activities sooner, including playing football.

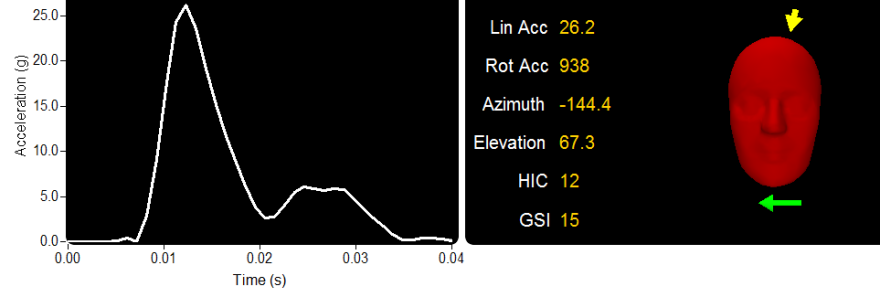

Steffen credits work done by the Medical College of Wisconsin, which used sensors inside Concordia player helmets to measure where on the head a player was hit and with how much force. Since 2014, the Medical College, Indiana University's School of Medicine, the University of Michigan and the U.S. military academies have been partners in what's known as the CARE Consortium. With $30 million from the NCAA and Defense Department, phase one of the consortium's research focused on the short-term effects of concussions.

The Medical College's Mike McCrea says that phase found "it was taking more people longer to recover than what we had thought years ago."

This fall, the NCAA and federal government have granted another $22 million for phase two, with the Medical College getting about one-third of the amount. McCrea says CARE 2.0, as he calls it, will look at any long-term effects of concussions.

"And determine, OK, what are the effects of a four to five-year career as an NCAA student-athlete or military service cadet in training on neurological and psychological health," McCrea said.

McCrea says the results could help inform not only college and high school parents but also those with younger kids just maybe starting to play soccer.

But a study released last week by the UW-Madison found high school athletes with limited access to athletic trainers are far less likely to have concussions identified and managed properly. That, plus some parents are calling for contact sports like football to be banned. But McCrea says more sitting around doesn't sit well with him.

"We are in our poorest physical and psychological health than at any time in the history of this country. So, the notion of fewer young people participating in healthy activities such as sport is more disturbing to me frankly than the potential long-term risks associated with injury," McCrea said.

Instead, McCrea says he expects more changes in training and rules to protect the players, while waiting, perhaps, for equipment improvements.

McCrea is also about to co-lead a national study on long-term health consequences for former NFL players who suffered repeated concussions while playing the game.

Support is provided by Dr. Lawrence and Mrs. Hannah Goodman for Innovation reporting.

Do you have a question about innovation in Wisconsin that you'd like WUWM's Chuck Quirmbach to explore? Submit it below.

_