The number of GED graduates at Milwaukee’s main test sites plummeted beginning in 2014, the year a new GED test — a computer-based exam that focuses on higher-order thinking — was adopted across the nation. Still, educators agree that the new test assesses the skills that are needed to succeed in today’s workplace, and the passing rate has improved — from 47 percent in 2014 to 72 percent in 2016.

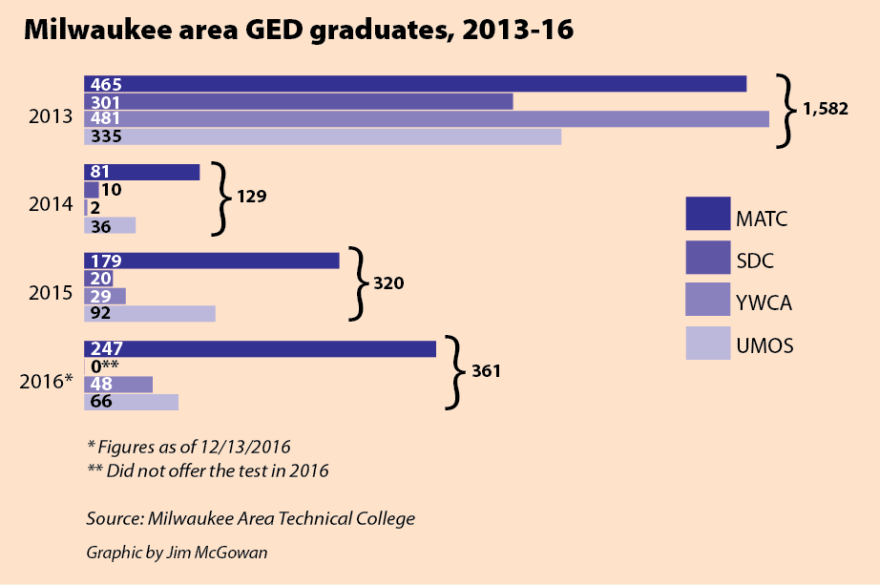

In 2013, the last year of the old test, 1,582 students passed at the four Milwaukee testing sites — Milwaukee Area Technical College (MATC), Social Development Commission (SDC), YWCA and United Migrant Opportunity Services (UMOS), according to data provided by MATC. In 2014, only 129 students passed.

The most dramatic drop occurred at the YWCA site, where 481 students passed the test in 2013, and only two did so in 2014. A representative at YWCA Adult Education did not respond to requests for comment.

“The consequences of the change in the first few years has been devastating,” said Tony Tsai, education manager at UMOS. “[Passing] this test is critical in the fight against unemployment and poverty.”

According to Tsai, one of the problems was that the new test was rolled out before anyone — students and instructors included — was ready.

“There was a big learning curve in terms of teaching people to critically analyze and pull information from what they’ve read,” Tsai said.

Juan Lopez, a Spanish language GED instructor at Journey House, 2110 W. Scott St., who funnels his students to the UMOS testing center, said his class sizes have dwindled since the change. Lopez, who is planning to host a graduation ceremony for three students this month, said only a quarter of the students he registers complete the course and end up taking the test.

“As the students start to face difficulties with the test or see that it’s not going to be as quick as they expected to get their GED they get discouraged,” Lopez said.

Lopez now splits his students into two classes so he can better assist those at lower reading levels with the more difficult material. He’s also developed new ways to explain the complex and abstract ideas to students at different levels. The writing test is one example of a change from the old GED, which used to ask testers to state their opinion on a subject. Students are now asked to compare and analyze two arguments and give reasons why one is better than the other, he said.

“Students definitely have a tough time adjusting to that change,” Lopez said.

Another challenge, he said, is that many of his students, most of whom are from Mexico, have limited experience working on computers and typically have an elementary- or middle-school education. The increased use of smartphones has helped mitigate some of the challenges associated with typing, but asking students to jump from elementary- or middle-school level to college is a huge step, he said.

The adjustment for teachers has been equally difficult, said Tsai. For the cadre of GED instructors at UMOS, which consists of one full-time teacher and eight part-time instructors supplied by MATC, it has taken a few years to become familiar with the material, he added.

Much of the problem, according to Regina O. Smith, dean of MATC’s School of Pre-College Education, and others, is that training for teachers on the new GED exam wasn’t available prior to the change, nor were the materials.

A more difficult GED

For the first time in its history, the new GED test was developed by a private company, Pearson VUE, which specializes in creating computer-based exams. Previously, the test was run by the American Council on Education, which is now partnering with Pearson.

The privatization of the GED test has drawn sharp criticism in some circles. Some educators have said that the more difficult exam is intended to send the message that graduating from high school is preferable to dropping out and obtaining a GED later. They describe the new test as yet another obstacle for low-income students.

The GED test, which consists of four exams — science, social studies, reasoning through language arts and mathematical reasoning — used to focus heavily on memorization, said Smith. The new test places less importance on recalling facts, and more on critical thinking.

“The need in the age of technology is for capable thinkers and people who can articulate their thoughts,” Smith noted.

The change was needed to help students prepare students for today’s careers or for higher education, said Dr. James Campbell, associate dean of MATC’s College of Pre-College Education.

Despite the noticeably smaller class sizes and smaller number of graduates, Lopez said his resistance toward the new test is waning.

“I think it [the GED test] is an eye opener for students. The process of taking the GED is making a higher education seem more accessible to them,” Lopez said.

Back in 2013, adult education specialists warned students who had passed some, but not all, of the tests required to obtain their GED that if they didn’t complete them before the new test was introduced they would have to start over. At the time, UMOS was running seven testing sessions a week for 20 participants at a time, recalled Tsai. Though class and testing session sizes are much smaller now, current students are much more likely to aspire to higher education, Tsai agreed.

“Increasing their education is the best chance they have at escaping poverty,” he added.

The new tests also offer three levels of passing. The first level signifies a high school graduate level; the second indicates that the individual is college ready; and the third that the student has skills comparable to a person who has taken some college classes. All levels signify that the individual is work-ready.

“Employers are looking for more high-skilled students and workers nowadays, and we’re working to give them a bigger pool to choose from,” Campbell said.

The number of students in Milwaukee who passed the test increased to 361 last year, up from 129 in 2014. The rate of students passing the test has also increased — from 47 percent in 2014 to 72 percent last year, according to data from the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction (DPI). Still, the number of Milwaukee students taking the test remains low, noted Tsai.

National trend

The drop in the number of students passing the new GED test is not isolated to Milwaukee.

Nationally, more than 540,000 passed the test in 2013, according to data from GED Testing Service (GEDTS). As in Milwaukee, the number of students across the nation who passed the new GED test plummeted in 2014; Just 86,000 students passed the test that year, according to an article published in the Washington Post.

There are a number of reasons for the drop, say educators, including an improved economy — which may make it easier for high school dropouts to find work — the higher price and the test’s difficulty.

The cost to take the GED test rose from $80 in 2013 to $135 in 2014, which has been an obstacle for students. “We were in the middle of a recession. Students had to make a choice between feeding their families and going to school or paying for a test,” Campbell said.

UMOS, the YWCA and SDC offer most students enrolled in their prep courses stipends to take the GED test. But, students are not guaranteed a reduced price or free tests, especially those who failed on their first try.

The Wisconsin Technical College System purchased a large number of practice tests, which cost $6 a piece, for community organizations administering the GED and MATC testing centers, according to Campbell. UMOS also received a large donation of GED prep books and practice tests from Wisconsin Literacy, Inc. Journey House charges students a discounted price of $3 for the practice tests.

Another problem with the rollout was that, at first, students could only pay for it with a debit or credit card, Campbell said.

MATC, which provides about 80 GED instructors at 35-40 locations, including the Milwaukee County House of Correction and halfway houses, is looking to emulate partnerships such as the GEDTS agreement with Walmart. Walmart covers the costs for its employees to take the GED test, viewing it as a way to decrease turnover and increase advancement of its workers.

Reason for hope

Tatiana Roche, 23, is a working mother of two children, ages 1 and 3. Responsibilities at home led her to drop out of high school and since then she has been stuck working a series of low-paid waitressing and cashiering jobs. Last year, she decided to stop putting off her dream of going to college and studying criminal justice.

“I knew I had potential,” Roche said.

High scores on her pretests boosted her confidence, so she scheduled the tests. She initially struggled with the math test, but has now passed them all, and is looking to begin college in the fall.

“Now my kids will see me succeed in school and be more successful in life,” Roche said.

Jerome Montalvo also sees passing the GED as a stepping-stone to a future career.

Montalvo, 19, had dropped out of South Division High School to work and earn money, a decision he said he soon regretted.

“I was working hard and seeing other people who’d been there for years still making minimum wage,” he said. “I want to be somebody, not work for a factory all my life.”

Montalvo, who plans to complete his GED test in June, plans to enroll in the Culinary Arts program at MATC. His goal is to become a head chef someday.

Montalvo and Roche credit much of their success to Maria Madrigal-Alvarez, a GED instructor at UMOS. Madrigal-Alvarez, who’s been working at UMOS for 12 years, said she’s gone through many of the growing pains associated with the new test.

She recalls losing nearly all of the students she’d worked with prior to the change. But, most of her current students don’t even know it occurred, she said. Like Lopez, she continues to adjust her teaching to better prepare students to the test, which is still changing. For example, the essay portion was removed from the social studies test, and the passing score was lowered for all tests in 2016. She has the students balance their time between subject areas they’re strong and weak in. The weak subject is typically math, she added.

“I have them work an hour on reading and then on math, which helps them build confidence and improve on both at the same time,” Madrigal-Alvarez said.

She said today’s students are increasingly tech savvy, which eased the transition to the computer-based exam.

“They also have higher career goals, which motivates them to work harder,” Madrigal-Alvarez said.

Lopez and Madrigal-Alvarez agreed that the process of preparing for and passing the new GED test makes a higher education seem more accessible.

“Students are also more likely to succeed in higher education,” Lopez said. “I also hope that employers realize when they’re hiring or interviewing GED graduates that they have a higher level of critical thinking and much higher skills compared to those who passed the old test.”