It's been five years since one of the most heinous racial killings in U.S. history when a white supremacist murdered nine worshippers at the historic Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, S.C. The massacre shocked the nation and prompted a racial dialogue in the city.

Those same issues resonate today amid the national outcry over recent incidents of police brutality.

Ethel Lee Lance, 70, was at Emanuel AME for Wednesday night Bible study on June 17, 2015 when a white stranger showed up, her daughter, Rev. Sharon Risher recounts.

"They welcomed him in," Risher says. "He sat there and listened to this whole Bible study. And when they were in a circle holding hands in prayer is where he took out his Glock 45 and commenced to shooting and killing them like they were animals."

He fired 70 rounds. Risher's mother, two cousins, and a childhood friend were among the nine people killed. They include: Clementa C. Pinckney, 41; Cynthia Graham Hurd, 54; Susie J. Jackson, 87; DePayne Vontrease Middleton-Doctor, 49; Tywanza Kibwe Diop Sanders, 26; Daniel Lee Simmons Sr., 74; Sharonda Coleman-Singleton, 45, and Myra Singleton Quarles Thompson, 59. Three others survived: Felicia Sanders, her granddaughter, and Polly Sheppard.

Risher says the killer intended to snuff them out because of who they represented.

"Just like everybody else that's been killed because of hate and race, we need to continue to remind people that we continue to be hurt when all we want to do is be a people that could thrive like everybody else," Risher says.

Lessons learned from Charleston massacre

Risher has written a book about finding hope after the Charleston massacre and travels the country telling her story. Now she questions whether the nation has learned anything in the past five years since the shooting.

She says recent police killings of George Floyd in Minneapolis, Breonna Taylor in Louisville, Ky., and Rayshard Brooks in Atlanta show a systemic disregard for black lives.

"I'm just weary," Risher says. "Even though I know everybody is not a racist and there are people in this country that do want racial harmony, it's just so much to get through. You wonder. How long? Just how long?"

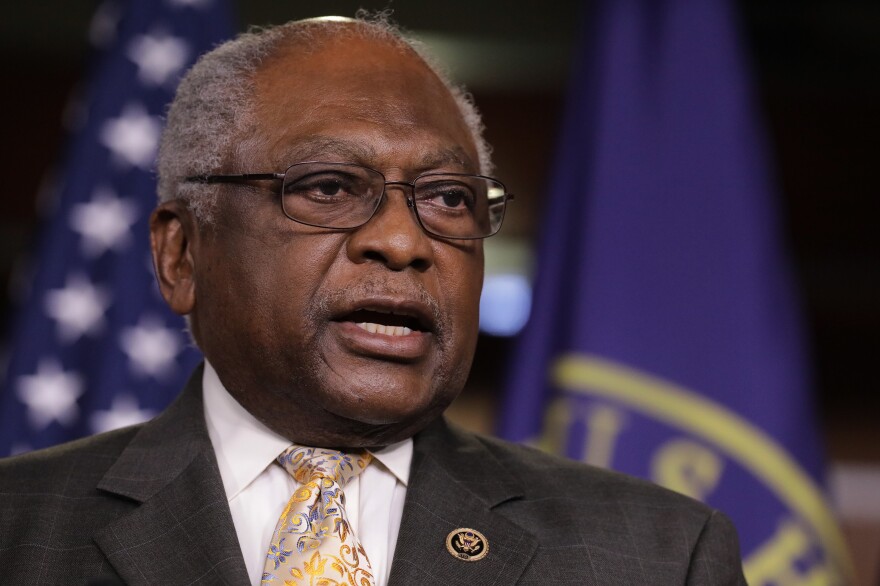

Emanuel AME is known as Mother Emanuel. Formed in 1816, it's one of the oldest black churches in the South, and survived being burned down for its role in an 1822 slave revolt. South Carolina Congressman James Clyburn, the House Majority Whip, says that's why a white supremacist targeted the congregation.

"And undertook what he thought would ignite a race war," Clyburn says. "What he did do ushered in a re-examination of who and what we are as Americans."

Shooter Dylann Roof was convicted on federal hate crimes, for which he was sentenced to death, and also pleaded guilty to state murder charges. Before the Emanuel massacre he had posted a racist manifesto online saying he was "awakened" by the 2012 killing of Trayvon Martin — the 17-year old African American shot to death by neighborhood watch volunteer, George Zimmerman, in Florida. Roof had posed for photos with Confederate flags.

After the mass shooting, there were ensuing battles over Confederate imagery, and groups formed to foster deeper interracial dialogues across South Carolina. Similar to what is happening now, Clyburn says.

He's among those in Congress, including Republican Sen. Tim Scott of South Carolina, who are calling for federal legislation to address police brutality. Clyburn points out that after the gruesome Emanuel attack, there was no lethal force, let alone violence when police apprehended the shooter Dylann Roof.

"The police officer that approached the door of the automobile he was driving, he re-holstered his gun," Clyburn says. "He didn't point it. He re-holstered his gun. There was tremendous difference in his arrest and what we've seen the last several days."

Dash cam video shows several officers backing away while one helps Roof out of the driver's door and handcuffs him.

'It was just a major loss'

"It was unspeakable," says the Rev. Kylon Middleton of Charleston's Mount Zion AME Church.

He was lifelong best friends with Emanuel pastor Clementa Pinckney, who was killed in the massacre while Pinckney's wife, Jennifer Pinckney, and one of their children huddled in the church office near the Bible study as the shooting was happening. Middleton now helps run a foundation in Pinckney's memory.

"Our lives were so intertwined that it was just a major loss," he says. "It was literally losing a brother."

Middleton says he was outraged at the way Roof's arrest went down, and what happened after. Once he was jailed, police brought Roof a meal from Burger King.

Just two months prior a white police officer in North Charleston shot and killed Walter Scott, as the African American man was running away after being pulled over for a broken brake light.

Middleton says it took the church setting to show that racial injustice was real – that black people could be targeted even though they were doing nothing wrong. But he says it was short-lived.

"That moment of 2015 was not sustained because there were so many things beyond the veneer that still needed to be dealt with," Middleton says. "It needed to be ripped away or stripped away or exposed and truly put on the table. So that those hard conversations could happen."

Middleton helped lead a program called the Illumination Project, designed to build trust between black communities and Charleston police. But he says every new cellphone recording of police brutality from anywhere serves as a setback to progress.

He says the protests for racial justice today, underway for more than three weeks now, including in Charleston, have the potential to become a full-fledged movement.

Hopeful the nation has reached turning point

The Rev. Anthony Thompson agrees. He's the pastor of Holy Trinity Church in Charleston, and lost his wife Myra, a lifelong member at Mother Emanuel.

"I mean, my wife must have been on every committee in that church," he recalls fondly. She was soon to be ordained as a pastor and was teaching the Bible study that night.

Thompson has been dedicated to reconciliation initiatives since the mass shooting. He says it forced a reckoning with Charleston's history, and demeanor.

"The city was built on the back of slaves, so racism has always been a problem here," Thompson says. "We are very hospitable city. You know, where we smile and we laugh, but there was always an undertone of racism about which we would never talk about. And none of this came to focus until the Emanuel nine tragedy."

Now he's hopeful the nation has reached a turning point.

For Sharon Risher, the test for the movement taking root today is whether people are prepared to endure disruption.

"We have a tendency to be emotionally reactive when these things happen, and we go on for a couple of weeks and we get the hashtags," she says. "But when it comes to the hard work, then I believe we retreat right back to our separate corners and live our lives."

Risher says maybe this moment will be the catalyst that unlocks lasting change.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAxODc1ODA5MDEyMjg1MDYxNTFiZTgwZg004))