Grasslyn Manor is a neighborhood within Milwaukee’s Sherman Park. Intense storms — increasing due to climate change — have fueled basement flooding there for decades.

But recently, neighborhood residents took the lead, working with the City of Milwaukee and Milwaukee Metropolitan Sewerage District to find a solution.

Identifying the problem

Steve O’Connell shares a conversation with a fellow Grasslyn Manor resident more than 15 years ago.

“[They said] 'You know Steve, I get this sewer stuff in my basement.' I’m like, 'What are you talking about?'...At that time, a regular rain would get sanitary in your basement. And so that’s what put me on to it. I’m like, this is no way to live, right in my own neighborhood,” O’Connell says

At the time, O’Connell was executive director of the Sherman Park Community Association. When he retired, he started digging in to what was causing the problem in his half-square-mile neighborhood.

O’Connell learned Grasslyn Manor sits atop a historic waterway that feeds into a historic wetland. The waters haven’t gone away. They’ve just been “pushed” beneath the surface.

“So our water table is very high,” O’Connell says.

Cracked or root-bound pipes and, in some cases, storm sewers incorrectly hooked up to sanitary sewer lines make Grasslyn Manor even more susceptible to flooding.

Residents couldn’t do anything about more frequent rain due to climate change. They couldn’t change that their houses were built on soggy land, but the sewer problems —maybe that, they could fix.

“We’re just neighbors trying to fix the problem. We needed professional help,” O’Connell says.

A plan of action

O’Connell connected with the Milwaukee Metropolitan Sewerage District and the City of Milwaukee. An action plan emerged. It’s a resident-led, neighborhood initiative that required building trust.

Thirty-three-year Grasslyn Manor resident Percy Burt helped make that happen.

He joined the fledgling neighborhood committee dubbed Help Build The Ark. It met every month for three years. They learned that when residents did get basement backups, most were not reporting it to the City.

Burt says many assumed the City wouldn’t help. Homeowners also worried their property values would plummet.

Burt and fellow volunteers went door-to-door. They handed out refrigerator magnets with straightforward advice about what to do and who to call to report flooding.

Burt shared his own story: His basement flooded repeatedly over the years, “Oh yes, a number of times. A minimum of three to four,” Burt says.

Volunteers didn’t rush the trust-building process. Neighbors were invited to share their stories and everyone received a handbook.

“It’s a team effort," Burt says. "We’re all in it together. And, it’s always some good that can come out of anything, you know? I know basically all of the neighbors now."

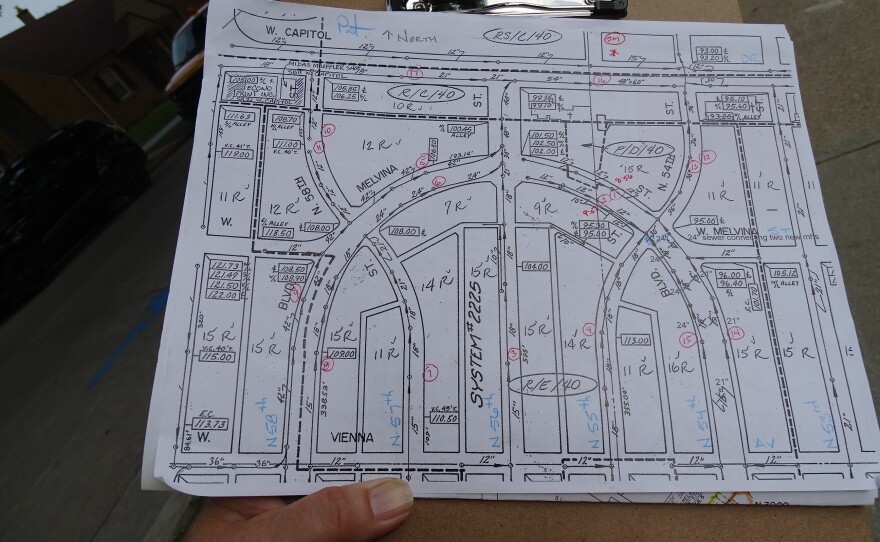

Last July, City engineering technician Pat Eucalano and a DPW crew started investigating what was happening in the neighborhood’s sanitary lines.

The crew lifted each sanitary manhole and pumped smoke down the main. If the connection between the main and the home’s sanitary line is intact, smoke would come through what’s called the soil stack.

“So those little silver stacks that come out of the house, that’s what vents the toilet system. So, we want to see the smoke from the sanitary main — that we put in the sanitary main — we want to see that come out of the soil stack,” Eucalano says.

Then in August, historic flooding hit the Milwaukee area, including Grasslyn Manor.

Help Build The Ark happened to have a neighborhood picnic planned shortly after the flooding. Steve O’Connell hoped more families would join in on the project to address the sewer issues.

“We all have to be involved in this assessment. Look around, you say ‘Well, I’ve got six neighbors, they’re not here.' You knock on their door the next couple of days and say ‘Listen, I was at a meeting yesterday...We need to get involved.' You need to schedule them to come see your property,” O’Connell said.

Fatima Robinson was there despite being hit by the storm earlier that month.

“My hot water tank is gone and my washer is gone,” Robinson said.

Her mother lives next door. Robinson says although her mom spent $40,000 to protect her home from future flooding, “She’s still getting water. To spend that much money and to think that you’re safe, and then it still floods — it’s devastating,” Robinson says.

Robinson and her mom were among the Grasslyn Manor residents who signed on for the next phase of testing.

That included flushing red dye down their basement toilets.

Outside in the street, raSmith engineer Anthony Hindick peers down into the sanitary main, hoping the dye will start trickling through. “I take note of when they the enter the house and then I just keep watch," he says.

Moments later, "I can see the red already trickling. It’ll get stronger and stronger as it keeps going," Hindick says.

That means the plumbing inside the house is delivering wastewater where it belongs.

There’s more to the assessment, including checking downspouts.

“The reason why additional testing takes place is if for some reason these downspouts were connected to the sanitary sewer — that’s what we don’t want,”Kate Jankowski with raSmith says.

The local engineering firm assisted Milwaukee's DPW on the Grasslyn Manor investigation.

More than half of the neighborhood’s 218 households participated in the assessment. Eighty percent need some sort of repair.

One key reason is the age of the homes and their infrastructure. After 70-plus years, laterals are wearing out.

The increasing frequency of rain, including during warming winters, and more erratic weather have only made the problem worse.

This week, the Department of Public Works will send residents its recommendations. For some homeowners it will mean replacing sanitary laterals, for others sump pump installations.

Work will begin this summer and stretch through 2027.

DPW anticipates 100% of the costs will be covered by an MMSD grant

Mike Duer calls the moment a milestone.

The 30-year Grasslyn Manor resident joined the neighborhood outreach effort from its inception.

“Steve found out I was retired and said, ‘Mike, I’ve got things for you to do,'” Duer says.

Duer knocked on his share of doors and helped install rain barrels. He encouraged neighbors to adopt storm drains to keep them free of debris.

Duer’s aspirations for Grasslyn Manor are about even more than flood control: “Hopefully it brings the community together," he says.

WUWM will check back with Grasslyn Manor as the project moves from plans to pipes.